Early Breast Cancer

Radiation therapy plays a critical role in the treatment of early breast cancer. Early breast cancer is treated with surgery followed by radiation therapy in most cases. The role of surgery, radiation therapy and chemotherapy has been progressively defined by the NSABP (now NLG) series in the US and the EORTC series in Europe. There remains controversy on when/if radiation can be omitted in breast conservation therapy and the relationship of age and treatment in local breast cancer.

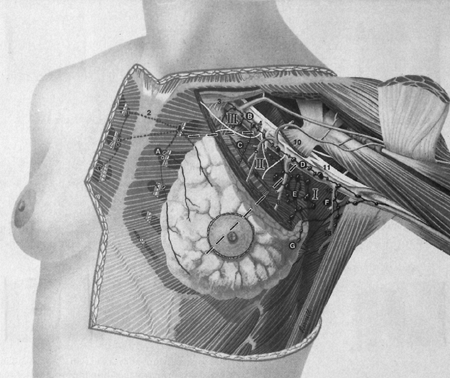

Anatomy

The breast is comprised of lobules and ducts for the production and transport of milk to the nipple. Most breast cancers start in the interface between the ducts and the lobules in the terminal ductal lobar unit. The breast has a rich vascular and lymphatic drainage network. Nodal spread patterns are important in breast cancer. The predominant lymphatic drainage is the axillary lymph nodes. There are three levels of axillary nodes: Level I: lateral to the pectoralis minor muscle, Level II, deep to the pectorailis minor muscle, and Level III medial to the pectoralis minor muscle. The Level III nodes are also known as the infraclavicular nodes. Breast nodal spread is directly along the path of drainage: first to level I nodes, then level II nodes and finally to level III nodes. Involvement of Level III nodes without disease in levels I/II is unusual. The next echelon drainage is to the supraclavicular nodes. Lymphatic drainage can also go to the internal mammary nodes, found 3 - 4 cm lateral to midline. Internal mammary node involvement generally occurs in the first three interspaces. Most breast cancers with nodal involvement, regardless of location of origin within the breast involve the axilla first. Breast cancers involving the medial, central or lwer breast drain more frequently to the INM chain than those in the upper outer quadrant, but the general pattern remains to the axilla.

Additional anatomy and nodal drainages are found in the Advanced and Metastatic Breast Cancer sections.

Epidemiology and Risks

Breast cancer is the most frequently diagnosed cancer in women. In recent years there has been much debate on the role of screening and treatment. Some have advocated that screening is overused, resulting in unnecessary treatment. The rate of breast cancer, presently in the US is 229,060 cases/year. Some of this is due directly to population screening. Unfortunately, in 2012, estimated deaths from breast cancer is 39,920, the second ranked cancer related cause of death in women. Death rates from breast cancer have declined 2.3% between 1990 and 2007.

There are a myriad of proposed risk factors for breast cancer and scoring criteria such as the "Gail Model." Increasing age and female gender are the biggest risk factors for developing breast cancer. Other suggested risk factors are, personal history of breast cancer, nulliparity, late age at first childbirth, early menarche, late menopause, prio breast biopsy with hyperplasia, prior radiation history at a young age, post menopausal hormone replacement therapy, genetics. Body mass index appears to increase risk in post-menopausal women, but not pre-menopausal women.

The Gail Model uses epidemiologic risk factors: present age, number of first degree relatives with breast cancer, age at first birth, age at menarche, number of prior breast biopsies, and history of atypical ductal hyperplasia.

Genetic factors including BRCA1, BRCA2, p54 mutations are associated with breast cancer. There are a number of additional genes and syndromes also thought to be involved in hereditary breast cancers, including PTEN, BRIP, ATM, STK11 syndromes.

A number of studies have concluded that the use of Tamxoifen is preventive. The benefit of Tamoxifen was demonstrated in the NSABP (now NRG) P1 trials demonstrated that tamoxifen reduced the rates of both invasive and non-invasive breast cancer by 49% and 50%. This benefit was seen in all age groups and women who had a history of atypical ductal hyperplasia had a greater benefit of 86% risk reduction.

Prophylactic mastectomy is also used with similar impact on reduction in breast cancer development of around 89%.

Pathology and Natural History

Untreated breast cancer has a variable clinical course. Survival in untreated breast cancers is around 4% across all stages. Older data from the 19th and early 20th centuries were predominantly diagnosed at later stages. Treated (Halstead mastectomy) cases did considerably better at 34% survival. Estimates of tumor doubling time are about 5 years from malignant transformation to the development of a palpable lump. Most cancers develop in the upper outer quadrant, consistent with the distribution of breast tissue in the quadrants. The disease travels the ducts until it develops the ability to invade the basement membrane. It is capable of both lymphatic and vascular invasion. Invasion of dermal lymphatics results in a characteristic edema of the skin (peau d'orange). Less prominent skin dimpling can be caused by invasion of the suspensory (Cooper's) ligaments. Ulceration of the skin may take place.

Nodal Spread Patterns

General spread to the axillary nodes is common. For T1/T2 disease, nodal involvement averages between 10% and 40%. Factors include:

- larger tumor size, (> 1 cm)

- moderate or poorly differentiated nuclear grade

- Age < 60

- lymphovascular invasion

- high S phase fraction.

Primary Tumor Size

Nodal involvement probability is a function of tumor size. However, even tumors of size T1a (< 5 mm) and T1b (5 -10 mm) have significant nodal involvement. Occasionally, breast cancer is diagnosed with no invasive primary or no primary at all, and nodal involvement consistent with primary breast cancer.

Other Risk Information

Risk factors have been suggested for further refining the risk of nodal involvement: age, tumor size and grade. The ACS database multivariate analysis deemed large tumor size, younger age, outer half location, poor to moderate differentiation, infiltrating ductal histology, aneuploidy and African/Hispanic genetics as risk factors. Up to 30% of clinically node negative T1/T2 disease may have nodal involvement.

| 3 risk factors | 34% incidence of nodal involvement |

| 1 risk factor | ≤ 7% incidence of nodal involvement |

Older studies (NSABP/NRG B04) suggest that less than 1/2 of clinically negative but pathologically positive nodes will relapse in the axilla. The B04 study was a 3 arm trial that randomized to simple mastectomy v. simple mastectomy + ALND v. simple mastectomy + comprehensive chest wall irradiation. Node positive disease was 40% with > 97% nodal control in the axillary dissection arm, without radiation. The B04 outcomes are:

| Arm | Treatment | Node Pos. Rate | Axillary Recurrence |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | Simple mastectomy - no ALND | -- | 20% |

| II | Simple mastectomy and ALND | 40% | ≤ 3% |

| III | Simple mastectomy and CW/Nodal RT | -- | ≤ 3% |

Nodal control as the same as surgical control in the arm treated without axillary dissection but with radiation. It is reasonable to assume that about half of the involved pathologically positive axillary nodes will recur locally absent treatment, and that the rate of axillary node positivity is around 16% to 34% with at least some risk factors.

Internal Mammary Chains

The risk exposure and need for treatment of the internal mammary chains is one of the most controversial aspects of the treatment of breast cancer to date. There has been heated debates on whether or not the nodes need to be treated. Most major studies did include the IMN chains in the treatment algorithms, but the rate of failure in the IMN chains is low. Patients with positive IMN nodes had a significantly worse overall prognosis at 20 years than those who did not. However, clinical failure in the IMN is rare, despite the evidence of pathologic involvement. Most studies report IMN patterns of failure at < 1%.

Risk factors for IMN include tumor size (p < 0.0001) and number of postive axillary nodes (p < 0.0001), but not with age or primary location. Veronesi (Milan) found that tumor size > 2 cm and age < 40 with positive axillary nodes had a 41% risk of positive IMN nodes on dissection. With negative axillary nodes, the risk was 16%.

Supraclavicular Nodes

Supraclavicular involvement is associated with high axillary nodal involvement or IMN involvement. Younger age (≤ 40 years) tumor size (> 3 cm), angiolymphatic invasion, ER negative were signfiicant for predicting supraclavicular metastases in one study. Using multivariate analysis, these factors were reduced to the following:

- high histologic grade

- > 4 nodes positive

- Axillary levels II/III involvement.

In patients with 4 or fewer Level I axillary nodes, the supraclavicular node incidence rate was 4%. If the level III axillary nodes were involved, the rate increased to 15.1% Clinical failure in the supraclavicular nodes, and is dependent on the extent and location of axillary nodal involvement. In patients with 1-3 axillary nodes positive and opposed tangent treatment alone, the risk of failure in the supraclavicular region is 1.3%

If there are 4 or more nodes positive several studies report that untreated SCN may fail at as high as 20%. A study of 1031 patients treated with mastectomy and Level I/II ALND followed by adriamycin based chemotherapy without radiation reported SCN failure rate at 10 years of 8%. Predictors of SCN failure in this study were: ≥ 4 LN positive and gross extranodal extension. In these groups, the SCF failure rate was 14% - 19%. Radiation treatment of the supraclavicular fossa in the higher risk patients resulted in very high local control rates of < 1% failures.

Distant Metastases

Micrometastases are detected in about 30% of patients with Stage I-III breast cancer. At 5 years patients with micrometastases had higher rates of lymph node metastases, ER/PR negative tumors and higher grade tumors. Micrometastases portends poorer overall survival with a relative risk of 2.15, poorer disease free survival (RR 2.13) and distant DFS (RR 2.33).

The role of local control and distant metastases

Without local/regional control there will be no distant control. Optimizing local control can impact systemic metastasis and survival and systemic treatment can impact local control. Studies have shown significant improvements in local, regional and systemic control with the use of radiation therapy, chemotherapy and hormonal treatment (and of course, surgery). Appropriate multimodal integration of therapies is important to optimize overall outcome. For early stage disease, the rate of distant metastases ranges from < 5% for T1a disease with well differentiated histology to > 40% for T2 tumors with poorly differentiated disease and pathologically involved lymphatics. Some argue that local/regional recurrence is a harbinger of distant metastases (Fisher NSABP/NRG B06 analysis), rather than the cause of distant metastases.

Meta-analyses have demonstrated a small but significant impact of local control on systemic metastases and overall survival. One meta-analysis compared BCS ± radiation therapy demonstrated a 300% reduction in the risk of local relapse and an 8.6% improvement in mortality with the addtion of radiation. The EBCTCG analyzed studies containing over 42,000 women in 78 trials to see if the 5 year local control risk difference exceeded 10%. Where the 5 year local relapse risk was < 10%, there was no impact on 15 year overall survival. But, where that risk was > 10% (25,000 women), the difference in local control risk was 5% v. 26% and the 15 year cancer mortality risks were 44.6% v. 49.5% (p < 0.00001). Overall, the addition of radiation reduced the risk of breast cancer death from 25.2% to 21.4% and was statistically significant (p < 0.0001). The 10 year risk of first recurrence was reduced from 25% to 19%. In node positive disease, radiotherapy reduced the 10 year risk of recurrence from 63.7% to 42.5% and the 15 year risk of breast cancer death from 51.3% to 42.8%. Overall, the ECBTCG meta-analysis shows that one breast cancer death was avoided by year 15 for every four recurrences avoided by year 10.

Clinical Workup and Evaluation

The majority of early breast cancers are assymptomatic and are found on screening mammogram. Of those that do present clinically, there is a painless or slightly tender breast lump. As the tumor advances breast tenderness may develop or become more generalized with local skin changes, or a nipple discharge which may be bloody. Patients with early breast cancer rarely present with distant metastases or clinically palpable axillary lymph nodes.

There is significant debate on whether delays in diagnosis and treatment make a difference. Multivariate analysis shows a longer duration of symptoms had a highly significant adverse impact on survival, but this difference went away when stratified by stage and tumor size. Other studies note that delays in diagnosis or treatment of 6 - 12 months led to increased risk of larger tumor and more lymphatic involvement, compared wtih promptly initiated treatment within 4 - 12 weeks of the original abnormal screening mammogram.

Screening Mammography

Screening mammography has been used since the HIP-NY study of the 1970s. 8% of all screening mammograms result in a request for addtional studies. 1% will go on to biopsy and 0.3% will be confirmed breast cancer. There is a large body of evidence that screening mammograms reduce breast cancer mortality rates. Many agree that the appropriate age to start screening mammograms is 40 and most agree that 50 and older should have them. The HIP-NY demonstrated benefit at all ages from screening but a greater benefit between ages 50-59. The study included women aged 40 - 64. The breast cancer mortality rate was reduced by 1/3 in the screened women. A similar study in Sweden showed similar results: 48% reduction in breast cancer mortality in the screened population. A Canadian study arrived at the opposite conclusion in mammograms in women age 50-59. The Canadian study has been widely criticized for its quality, unbalanced allocation of women with advanced cancers, poor quality of mammography and insufficient sample size of 107 in the screened group and 105 in the PE only group.

Diagnosis and Workup

Once a breast mass is identified on screening tools, a complete cliincal and family history is in order. Focus on gynecologic history including menstrual parameters, pregnancy history, and hormone use, and other risk factors. The breast exam should be both sitting and lying to confirm masses. Careful examination of both breasts to note changes in size, pigmentation, scaling nipple discharge, location, size, mobility, tenderness of any masses. Likewise the axillae and supraclavicular fossae should be examined and palpated.

If the screening mammogram is positive, a diagnostic mammogram is usually recommended. The screening mammogram consists of a craniocaudal view and a mediolateral oblique view. Diagnostic mammograms characterize detected abnormalities with magnfication views and possibly other additional views. These may be needle localized for planned biopsies. Clusters of microcalcifications are associated with DCIS. Frequently an ultrasound follows a positive diagnostic mammogram to further characterize the mass. An ultrasound guided biopsy may be obtained.

Biopsy and Pathology

Core needle biopsy or excisional wire localized lumpectomy/biopsy are generally performed. Biopsy of any suspicious mass is mandatory. For wire localized excisional biopsy, the localization wires should be left in place and a specimen mammogram should be obtained to insure all microcalcifications are removed. The specimen should contain orienting landmarks placed by the surgeon at the time of the procedure. ER and PR receptors should be assessed and HER/neu should also be determined for most breast cancer histologies.

General Management and Treatment

Management of breast cancer is interdisciplinary, and based on the pathologic and clinical extent and characteristics of disease.

Surgery

Primary tumors may be managed surgically by lumpectomy or mastectomy. Nodal regions are addressed by lymph node dissection or sentinal node biopsy. The following surgical managements are used:

- Radical mastectomy (Halstead)

- no longer used due to the results of NRG/NSABP B04

- Extended radical mastectomy

- Modified radical mastectomy

- Simple mastectomy

- Skin sparing mastectomy

- Standard mastectomy with limited skin sacrifice to aid in immediate reconstruction.

- Nipple sparing mastectomy

- Nipple areolar complex is preserved. This is not routinely employed in breast cancer surgery.

Breast conserving surgery consists of the following:

- lumpectomy, partial mastectomy, quadrantectomy

- all are similar procedures

- Re-excision to clear margins is indicated if margins are positive

Influence of Surgical Margins

Surgical margins have been debated with the key question: What is a clear margin and what margin is a "good enough margin?" The NSABP studies have all defined negative margins as no disease at the inked tissue margins. The necessary margin has been debated. Most recently in 2014, a joint ASTRO-SSO Consensus guideline has been developed.

ASTRO/SSO Consensus Guideline for Breast Conservation Surgery Margins:

- Positive Margins

- Defined as ink on invasive tumor or DCIS which is associated with a doubling of the risk of recurrence with/without radiation.

- Negative Margins

- • Negative Margins optimize the risk of ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence.

- • Wider margins do not significantly lower this risk further.

- • The routine practice of obtaining wider than negative margins does not significantly lower the risk of recurrence.

- • In patients not receiving chemotherapy there is no evidence suggesting wider margins are needed.

- • Wider margins are not indicated based on histologic subtype.

- • The choice of radiation fields, dose, fraction and boost dose should not depend on margin width.

- • Wider margins are not indicated for invasive lobular cancer.

- • There is no evidence that wider margins in younger patients (≤ 40) decreases risk of recurrence.

- • When negative margins are present in extensive DCIS, there is no evidence of increased risk.

Mastectomy or Breast Conserving surgery in early breast cancer?

For most patients with early breast cancer, either option is reasonable. All available evidence demonstrates good local control and survival with either treatment. For patients who wish to avoid radiation, a mastectomy is more likely to eliminate the need for radiation. Mastectomy is likewise preferable for those who have large tumors and a lumpectomy would result in poor cosmesis. Other indications for mastectomy include diffuse disease within the breast, inability to obtain clear margins and patient preference. There is a trend toward lumpectomy which is continuing. The availability of local radiation did not appear to influence the decision process.

Surgical Management of the Axilla

Axillary node dissections were a standard component of staging for the majority of women with early stage breast cancer. Sentinel node biopsy has replaced comprehensive axillary dissection in more recent times. Currently, positive sentinel nodes indicate a need to do an axillary dissection. A completion axillary dissection will be most useful for women who's treatment course will be changed with respect to systemic therapy depending in findings. Axillary dissection or radiation results in a high rate of local control in Sentinel node positive patients.

Approximately 20% to 40% of early breast cancer patients have pathologically positive nodes in the setting of clinically negative nodes. Axillary recurrences in undissected, untreated axillary nodes is about 20%. There is some discussion that very favorable risk patients may not need a staging axillary dissection: mucinous, medullary, and tubular histologies, small focus of disease (T1a/b) and older patients. Lymph node positivity is increased significantly in high grade disease.

Sentinel Node Biopsy

Sentinel node biopsy allows the avoidance of ALND. The ACOSOG Z11 trial has suggested that SNB provides adequate staging so that further surgical management of the axilla is unnecessary. Traditionally a positive SNB has lead to a completion ALND. All patients in the Z11 received whole breast RT, but there is uncertainty on whether or not fields were modified to cover the higher axillary nodes (high tangents). SNB is highly accurate for staging with a sensitivity of 91% and accuracy of 97%.

Breast Conservation Surgery without Radiation Therapy in the Elderly

There has been much debate on whether or not radiation can be avoided in older women. Radiation therapy after lumpectomy has been the standard of care for nearly 3 decades. Early NCIC and CALGB studies addressed whether radiation therapy can be avoided in select populations of older women. Both of these studies failed to demonstrate the safety of avoiding radiation therapy, provided life expectancy was greater than about 8 years or so. Omitting radiation in post lumpectomy patients increases the risk of recurrence by a factor of 3, and there is an evolving body of evidence that these recurrences may impact survival.

The CALGB trial (Hughes) randomized 636 women with Clinical Stage I, ER positive breast cancer to:

- Arm I: lumpectomy plus tamoxifen plus radiation

- Arm II: lumpectomy plus tamoxifen alone

The only significant difference between the two groups was the rate of local control at 5 years. The local recurrence rate was 1% in the radiation arm and 4% in the tamoxifen alone arm. This difference was statistically significant with a p < .001. There were no signficant differences in mastectomy free survival distant mets or OS5. More recently Hughes updated this study in 2013, which showed no difference in overall survival at 10 years, but 98% in the tamoxifen + radiation arm were free of local and regional recurrences, whel 90% were in the tamoxifen alone arm. (J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2382-7)

Fyles NCIC study looked at women ≥ 50, T1/T2 node negative patients treated with lumpectomy + tamoxifen ± radiation. At 5 years, tamoxifen alone arm had a 7.7% recurrence and the radiation arm had a 0.6% recurrence rate. The DFS5 rates were 84% in the no radiation arm and 91% in the radiation therapy arm. A subgroup analysis restricted to T1 disease showed similar benefits. These results also applied to axillary recurrence rates. The axillary recurrence rate in tamoxifen alone as 2.5% and 0.5% in the radiation arm.

A SEER review by Smith for women aged 70 and older with small, node negative ER positive cancers tested whether radiation therapy was associated with ipsilateral breast cancer recurrence or subsequent mastectomy. The SEER review had similar results to the CALGB and NCIC studies. The SEER review concluded that radiation therapy was associated with an absolute risk reduction of 4 events/100 women at 5 years and 5.7 events/100 women at 8 years (8 events without radiation to 2.3 with radiation, p < 0.001). Using a comorbidity analysis, Smith concluded that radiation therapy was most likely to benefit women 70 to 79 years old, who had no other comorbidities. Not surprisingly, women 70-79 with significant comorbidities were least likely to benefit.

The above studies indicate that the benefit of radiation therapy for elderly women is significant in terms of local control, but this absolute beneift is relatively smaller and must be weighted against comorbidities. For women with multiple life-shortening co-morbidities, tamoxifen alone is likely adequate. For women in otherwise good health and long life expectancy, it is reasonable to offer radiation to women over 70 eith ER positive tumors. A second caution before deciding against radiation is the compliance rate of tamoxifen should be discussed before deciding to omit radiation in breast conserving treatment.

Systemic Treatment: Cytotoxic Chemotherapy and Hormone Manipulation

Chemotherapy plays an essential role in the treatment of early breast cancer, including node negative breast cancer. Systemic therapy has been shown to reduce the risk of relapse and mortality. More recently, multi-gene markers (Oncotype DX) have been shown to predict better the benefit (or lack of benefit) from chemotherapy. Chemotherapy is more likely to be required in triple negative breast cancers. There are an increasing variety of choices for conventional chemotherapies, including CMF (older), doxorubicin+cytoxan followed by taxotere, Cytoxan-taxotere, and more. Herceptin (trastuzumab) is used in H2N (her2/neu) positive breast cancer.

Radiation Therapy

Radiation therapy plays a central role in breast conserving therapy and in most mastectomy surgical approaches. Breast conservation is generally appropriate when good cosmesis and clear margins can be obtained and there is no contra-indication to radiation. For breast conservation, a wide local excision of the primary tumor with clear margins, axillary node staging and if necessary, an axillary node dissection followed by breast radiation therapy is the typical course. Breast radiation is generally carried out using opposed tangent fields to a dose of 45 to 50 Gy at 1.8 - 2.0 Gy/fraction. A boost is then delivered in most, but not all cases to the scar/cavity plus a 2 - 2.5 cm margin. If a positive margin is found, a local re-excision to clear margins is reasonable. Using 3D conformal radiation nomenclature, the GTV is the tumor bed, defined by seroma cavity, clips or both. The CTV is a 1.5 cm expansion on that, corrected for anatomical barriers to spread. The final PTV is a 0.5 mm expansion on the CTV (or a 2 cm expansion on the seroma cavity).

Conservation of the breast with optimal cosmetic results and no recurrence is the ideal outcome. Optimal cosmetic outcome is associated with improve psychological adjustment in cancer survivors and is an important part of survivorship. Breast conservation surgery is now widely accepted, based on numerous studies showing at least equivalence to more radical surgery.

Appropriate candidates for breast conserving surgery should take into account the importance of cosmesis. Appropriate candidates include an interdisciplinary consultation with the surgeon, the radiation oncologist and the medical oncologist. Despite clear and mature evidence of equivalence, some patients will choose a mastectomy. In these patients, the possibility of a need for post-mastectomy radiation should be discussed, in the event unexpected adverse pathologic features are present. Also, Canadian and European Studies (NCIC and START) have demonstrated equivalence to mildly hypofractionated treatment of the breast at 2.66 Gy/fraction to 42.5 Gy in 16 fractions to conventionally fractionated radiation. At present it is unclear whether or not there is a benefit to a boost. There are two ongoing studies attempting to address this: The TTROG study and a newly opened RTOG/NRG study. Even if a boost is found necessary, the reduction in treatment from 33 - 30 treatments to 16 or 21 treatments is a significant savings, especially for women in rural communities. In addition, some women may be a candidate for accelerated partial breast irradiation, but this may be less attractive than the accelerated whole breast scheme, in that it is a BID treatment scheme, with a six hour interval, and there is localized cosmetic and fibrotic changes which may be less desireable than more uniform cosmesis associated with whole breast radiation.

Ideal patients will have a reasonably small tumor:breast size ratio, enabling clear margins without unacceptable breast size and contour changes. These tumors are generally < 4 to 5 cm, unifocal. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by lumpectomy and radiation for larger tumors has been shown to provide excellent results, thus opening women with larger tumors to breast conservation therapy. There are relative few contra-indications to breast conserving surgery. Patients with diffuse disease not amenable to resection or re-resection or patients with gross multicentric disease should proceed to mastectomy, primarily due to the poor cosmesis attainable after resecting all disease. Breast conserving surgery can be offered to most women with early breast cancer and a surprisingly high percentage of women with locally advanced disease.

Radiation Management of Early Breast Cancer

Standard Fractionation

Standard radiation therapy treatment delivers between 1.8 and 2.0 Gy/day for 25 - 28 days for a total dose of 45 to 50.4 Gy followed by a 5 to 8 fraction boost of 10 - 16 Gy. The cummulative dose is 60 - 66 Gy over 6 - 7.5 weeks. There is a growing trend toward faster, hypofractionated treatments, based on Canadian and UK studies demonstrating equivalent effectiveness and safety.

Hypofractionation

The UK trials (START A/B) randomized early breast cancer defined as stage pT1-3a, pN0-1 M0 disease to 50 Gy in 25 fractions at 2 Gy/fraction v. 41.6 Gy in 13 fractions at 3.2 Gy/fraction v. 39 Gy in 13 fractions at 3.0 Gy/fraction. The START A trial used a boost of 14 Gy at 2 Gy/fraction in 7 fractions to each of the regimens bringing the total dose to 57 Gy v. 55.6 Gy v. 53 Gy. The conclusion was the smaller number of fractions was as safe and effective as conventionally fractionated radiation.

The START B trial randomized similar patients to 50 Gy at 2 Gy/fraction v. 40 Gy at 2.67 Gy/fraction in 15 fractions with a primary endpoint of local tumor control. Local regional relapse at 5 years was 3.3% (50 Gy), 2.2% (40 Gy). A similar Canadian trial (Whelan) randomized women to 50 Gy in 25 fractions over 35 days or 42.5 Gy in 16 fractions over 22 days. His study excluded large breasted women (separations > 25 cm). The 10 year local regional relapse risk was 6.7% in the standard fractionation arm and 6.2% in the hypofractionated arm. The conclusion was hypofractionation was a non-inferior treatment. These studies did not include boost fields. There are two ongoing hypofractionated studies examining the role of boost in hypofractionation. The TTROG study, running for about 2 years and the RTOG study which opened in the summer of 2013. At present, the NSABP (NRG) studies dictate a boost in clinical trials when hypofractionation is used.

ASTRO stated hypofractionated whole breast radiaiton therapy was likely to be equivalent to standard fractionation in patients who met the following criteria:

- age > 50

- Stage T1-T2N0 treated with lumpectomy

- No systemic chemotherapy

- Dose homogeneity of 93%-107% (< 15% inhomogeneity)

The ASTRO panel favored a dose of 42.5 Gy in 16 fractions for patients not receiving a boost. There was no conclusion published concerning the role of a boost in patients treated with hypofractionation. The panel concluded that the heart should be excluded from the primary field when treating with hypofractionation due to uncertainty concerning the late effects on cardiac function.

Radiation Management of the Axilla

Clinicians differ widely in their approach to elective nodal treatment, particularly with respect to the internal mammary chains. Radiation therapy plays a role in the management of subclinical microscopic disease in the axilla and supraclavicular lymphatics. Nodal risk is in part determined by disease characteristics and the extent of surgical management. Surgical management is changing as a result of the success of sentinel node biopsy and studies such as ACASOG Z0011 which advocate for less surgical treatment of the axilla in the setting of positive sentinel nodes. There has long been debate and controversy over whether the internal mammary nodes should be treated. Opposed tangent standard radiation fields will generally treat a significant portion of the level I axillary nodes and high tangents will treat more and at least some of the level II/III nodes. There is little prospective randomized data to dictate clear guidance for the appropriate treatment of the nodal drainage basins. Studies are currently underway randomizing high risk node negative and node positive patients to chest/breast only or chest/breast plus regional lymphatics.

Perez and Brady (Goyal, Buchholz, Haffty) recommend the following for consideration of treatment of the regional lymphatics:

| Nodal Basin | Indications | Technique | Dose |

|---|---|---|---|

| SCN |

| RAO or LAO/imaging defined depth | 1.8 - 2 Gy/fraction 45 - 50.4 Gy |

| Axilla |

| RAO or LAO consider PAB if subotpimal coverage with AP | 1.8-2.0 Gy to 45 - 50.4 Gy |

| IMN | Consider for:

|

Partial wide tangents or matched e-/photon fields | 1.8-2 Gy to 45 - 50.4 Gy |

Axilla: Radiation or Surgery?

Prior to Sentinel Node Biopsy, full axillary dissection was the standard of care. SNB has proven both specific and sensitive. There are present questions concerning the role and need for axillary dissection in the SNB era. ALND has been demonstrated therapeutic with a risk of recurrence in the untreated axilla of around 20% in untreated axilla. Surgery has demonstrated a reduction (B04, Institute Curie, Guy I/II, Manchester I/II IBCSG, Milan) and thus is therapeutic. NRG/NSABP B04 was the first study to examine the role of reduced surgery in the treatment of breast cancer. The B04 study enrolled 1079 patients was followed for 10 years and had 40% positive lymph nodes. The study had three arms:

- Axillary dissection – 1% Axillary failure rate

- Axillary radiation – 3% Axillary failure rate

- Observation – 20% Axillary failure rate

Other respective reviews are consistent with this very old study. Haffty reported node control rates of 97% with radiation alone (no axillary dissection) at 10 years and 96% for the group with ALND treated to the supraclavicular and internal mammary nodes alone. ( IJROBP 1990;19(4):859-865). Haffty opined that axillary node dissection then was being increasingly used to determine the role of adjuvant chemotherapy, and concluded regional radiation alone without axillary dissection (to the supraclavicular and internal mammary nodes) resulted in excellent local control and was well tolerated.

Commenting on the ACOSOG Z0011 trial (Positive Sentinel Nodes Without Axillary Dissection: Implications for the Radiation Oncologist, JCO 2011; Vol 29 ), in which all patients underwent lumpectomy, sentinel node biopsy, no further axillary dissection, and tangent only irradiation — regional node irradiation was not allowed, systemic therapy as appropriate. The authors note that with the advent of multi-gene assays and markers, medical oncologists are relying less on the information from completion axillary dissection to determine the role of systemic therapy, thus there is less dependence on the axillary dissection data, even in the presence of confirmed sentinel node disease. They further note that radiation oncologists have also relied on ALND to determine the extent of radiation fields as the risk of involvement of Level III and supraclavicular nodes is a function of the number and characteristics of the axillary nodes. Radiation and axillary dissection does result in increased risk of lymphedema, but radiation to the undissected axilla carries minimal morbidity. Without surgical staging, though, increased uncertainty arises concerning the extent of radiation fields necessary to optimally treat breast cancer, particularly where questions concerning treatment of the regional nodes arise. In the comment, the authors recommend caution. They suggest that the tangent fields would have irradiated a large fraction of the axillary nodes (Levels I-III) and thus contributed to the lack of axillary recurrences reported in Z11. They estimate that standard tangents include 50% of the Level I nodes, 20% - 30% of the Level II nodes receive more than 90% of the prescribed dose, depending on patient anatomy, and the upper border of the tangent field. Z11 did not control and did not document the placement of the upper border of the tangent fields. High tangents in retrospective studies does cover a majority of the Level I/II nodes.

When ALND has not been performed and data to help assess the need for supraclavicular nodal irradiation is not available, other means must be used to determine whether or not to add extra fields to treat these nodes. Traditionally the SC field was added when the axillary dissection demonstrated ≥ 4 nodes positive and more selectively when 1-3 nodes were positive in higher risk disease. Without this information, predictive models may be useful in the setting of positive SNB but no axillary dissection. For patients that meet the criteria of ACOSOG Z11, high tangents, contouring the axillary lymphatics to determine coverage margins is reasonable. For higher grade disease that would not have met the Z11 eligibility criteria, targeting the remaining nodes in addition to level I/II undissected nodes is reasonable. Planning should include CT based nodal targeting with fields adjusted to cover the contoured nodes. Haffty recommends adding a supraclavicular field if the risk for Level III/SCN exceeds 30%.

The Canadian MA.20 trial randomized patients to breast radiation ± regional nodal irradiation. Most had 1-3 LN positive. This trial demonstrated improved disease free survival, local regional control, distant metastases control, and a trend toward improved overall survival, thus demonstrating the importance of regional nodal irradiation in patients who are at risk of having nodal microscopic disease which is undissected. Haffty indicates that prudence dictates treating patients who undergo breast conserving surgery, with SNB with suspected microscopic disease in adjacent lymphatics, provided it can be accomplished with minimal morbidity.

| Disease | SN + | SN # | Prob % add'l N+ | Prob N+≥4 | Technique |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IDC, 1 cm, ER+, LVIneg | N0(i+) | 3 | 3% - 8% | < 1% | Tangents |

| IDC, 1.8 cm, G3, ER+,LVIneg | N=1 | 2 | 24-27% | 2% | High Tangents |

| IDC, 2 cm, ERneg, LVI+ | 2 | 2 | 55-63% | 30 | High Tangents, consider full RNI |

| ILC, 4 cm ER+, LVIneg, multifocal | 2 | 2 | 64-77% | 40% | High tangents, consider RNI |

| IDC, 3 cm, ERneg, LVI+, mulitfocal | 3/ENE | 3 | 78-95% | 80% | Full regional nodal irradiation |

Many radiation oncologists favor regional nodal irradiation in cases where positive nodes are found. Some advocate foregoing RNI in case of 1-3 nodes positive. Most will recommend supraclavicular irradiation when there are four or more nodes positive. The NCIC MA.20 trial demonstrated distant and disease free survival and potential survival advantage with RNI.

The Internal Mammary Question

Internal mammary nodal irradiation can be summed up in one word: controversy!

A Yale series found no difference in DFS10 after BCS and radiation regardless of treatment of the IMN. Stemmer, et al in 2003 (JCO 2003;21(14):2713-2718) reported 100 node positive patients scheduled to receive IMN radiation. 33 did not received IMN RT due to technical difficulties. At 77 months followup DFS was prolonged in women receiving IMN RT compared to those who did not. Steffer also reported a trend to improved survival 78% v. 64%.

IMN treatment state of the art as of today: "Some say tomato, some say potato."

Sequencing of Multimodality treatments

The sequencing of surgery, radiation and chemotherapy creates a number of questions. Several studies have demonstrated an increase in the risk of local-regional recurrence with a delay in radiation beyond 8 weeks from surgery. the LRR5 was 5.8% if radiation was delivered ≤ 8 weeks compared with 9.2% if treatment was delayed 9-16 weeks, post operatively. This is retrospective data, a heterogeneous group of patients. A Joint Center trial investigated the sequencing of RT more formally. Patients were treated with BCS ⇒ adriamycin and cytoxan (AC) for for cycles, followed by radiation therapy in one arm or vice versa.

- Arm I: ACx4 → RT: 10 year event risk: 46%

- Arm II: RT ⇒ ACx4: 10 year event risk: 51%

This data was confirmed by MDACC and with Taxol, the CALGB.

Concurrent chemo-radiation has been tested and reported by Arcangeli and another study reported by Rousse and others. They conclude that concurrent chemo-radiation was slightly more effective than sequential, but at a cost of higher toxicity. These toxicities include a higher risk of radiation pneumonitis with weekly taxol, increased cardiotoxicity with bevasuzumab.

Hormonal sequencing also has controversy, because of the theory that tamoxifen may decrease tumor radiosensitivity. Radiobiological studies show tamoxifen stops cells in the relatively radioresistant G0/G1 phase. Overgaard reported increased imaging changes in lung tissue due to irradiation with patients treated while on tamoxifen and there are ER receptors in lung tissue, but there has been no reported symptomatic pulmonary changes. Three studies have demonstrated no difference in cancer related outcomes, but none reported toxicity measures.

Radiation Therapy Treatment Planning And Techniques

Treatment Position

The supine position is most commonly used on an elevated board to correct for the changing contour of the chest. Arms are placed over the head and immobilization is often used to insure reproducibility of postion. All breast setups are to some extent clinical. Some women with pendulous breasts may require additional support to prevent skin folds, provide reproducible breast positioning and permit better dose homogeneity. Others may require prone position, which poses a unique additional set of setup issues and adjacent tissue avoidance parameters. Once the treatment position is determined, for supine treatments, radio-opaque wires are used to identify the surgical scar and to delineate the clinical breast tissue region. The upper wire is placed at the head of the clavicle, the medial margin is mid-sternal line or slightly toward the contra-lateral breast. This wire can be used as a reference to setup up either an opposed tangent field or if IMN irradiation is contemplated, as a reference to alter the tangents to allow an electron field to be matched. The lateral margin should be at the mid-axillary line, modified to include palpable or imaging visualized tissue on a CT control scan. The precise location of this line is both clinically and imaging derived. The inferior border is marked at 2-3 cm inferior to the IM fold.

Treatment Parameters — The Breast

Patients should be treated with 6 MV photons unless there is wide separation, using opposed tangents. If there is a large breast (separation > 22 cm) higher energy (10 MV) may be useful to reduce inhomogeneity. Breast radiation homogeneity should be 93% to 105%. Missing tissue compensation (either mechanical or accelerator based "field-in-field") can be used in enhance dose uniformity. Bolus should be avoided in breast conservation.

By placing the patient on an elevated board, with the anterior chest wall parallel to the table top, and the inferior border half beam blocked to follow the chest wall contour. To maintain the ability to match an AP/AO field with the upper tangent field, the colimator should not be rotated. By elevating the patient appropriately, the deep portion of the field will match the downward sloping contour of the chest wall. Generally 2-3 cm of lung is included in the field, with the amount of lung greatly influenced by the clinical setup. The Central Lung Distance is a good proxy for the volume of lung irradiated. At 1.5 cm CLD, predicted lung irradiated by the tangent is 6%. AT 2.5 cm, the volume is 16%, and at 3.5 cm the volume is 26%. At deep CLD, (> 3 cm) cardiac volumes also increase signficantly in left breast treatments.

Special attention should be paid to the volume of heart irradiated. If the CLD is too great, a medial tangent breast port 3 - 5 cm wide may be added. The beam is angled 10 - 15 degrees laterally to conform to the angle of the medial main tangent. The heart should be blocked on the medial tangent. If this results in unacceptable breast sparing, a matching electron field may be used to supplement the tangent. An alternative treatment technique is the use of deep inspiration breath holds in patients capable of breath holding. If this technique is used, planning CT scans should be obtained for normal breathing first to avoid artifactually altering breathing patterns, followed by a deep inspiration breath hold. The information obtained will permit the assessment of improved dosimetry of breast and heart and selection of an appropriate technique.

Treatment Parameters — The Breast Dose

As discussed above, there are a variety of dose-fraction schemes, with hypofractionation coming into increasing used. The most common scheme is 2 Gy to 50 Gy 5 days/week. Others use 1.8 Gy to 50.4 Gy 5 days/week. Presently, the ASTRO Consensus Guidelines are quite selective in who is an ideal candidate for accelerated hypofractionated breast irradiation while freely admiting that the Consensus authors deviate from those guidelines. "For other patients, the task force could not reach agreement for or against the use of HF-WBI, which nevertheless should not be interpreted as a contra-indication to its use." ASTRO did say that the ideal candidate for HF-WBI had these characteristics:

- Age ≥ 50

- T1-T2N0

- No adjuvant chemotherapy

- Dose inhomogeneity within ± 7%

There was no concensus on boost. There is data indirectly from a report published in the IJROBP, December 2014 from Toronto, Sunnybrook which described HF-WBI in the treatment of DCIS. The Sunnybrook study reported that there was an 89% 10 year DFS compared with 85% 10 year DFS with conventional fractionation, but the data in the paper demonstrates a higher precentage of HF-WBI patients recieving a boost, compared with conventional fractionation, which could explain the difference between the groups.

Beam Energy

6MV photons are generally, but not always employed for tangents. Use caution when treating with higher energy beams to insure that the dose to tissue deep to the skin is adequate. Beam physics must be respected when choosing an appropriate beam energy. 3D conformal radiation planning techniques are important in determining when to use higher or mixed energies. Using forward planned tissue compensation techniques, improved dose homogeneity can be achieved without using older beam spoiler techniques or wedges, which will allow higher conformality and uniformity of dose in rapidly varying tissue surface contours. A reasonable dose homogeneity of between 5% and 8% should be achievable.

Target Volumes in the 3D conformal Era

3D-conformal radiation therapy is built upon the premise that irradiation is accomplished to a clinical target volume determined to be at risk for disease recurrence, persistence or progression. The nomenclature that has evolved since 1984 includes several volumes to identify what should be treated. In 1993, the ICRU codified that nomenclature in its ICRU Report 50 and supplemental report ICRU 62.

- GTV — gross tumor volume (volume of identifiable disease to be treated)

- GTV primary disease site

- GTV nodal disease site(s)

- GTV metastatic disease site(s)

- The GTV only exists if there is disease identifiable in tissue

- CTV — clinical target volume (volume of at risk tissue for residual/recurrent and microscopic disease )

- ITV — internal target volume (expansion of CTV/GTV which accounts for motion, shape deformation associated with physiologic processes)

- PTV — planning target volume which accounts for setup uncertainties

- TV — Treated volume: the volume actually treated to the prescribed isodose volume

- CI — Conformity index: ratio of treated volume / PTV (should equal 1, ideally)

There is no GTV in early breast cancer (because we have a lumpectomy with negative margins). The CTV has been well described in an RTOG atlas (RTOG Core Lab Contouring Atlas).

The atlas defines the breast CTV, Lumpectomy bed "GTV" which forms the lumpectomy CTV and node volumes. It also identifies chest wall volumes for post-mastectomy patients receiving radiation. The tag in parenthenses identifies the RTOG volume name as garnered from RTOG protocols.

- Breast CTV (CTV_WB) defines the breast tissue including the clinically apparent tissue (defined by wires placed at simulator time), the CT apparent glandular tissue, the lumpectomy bed as defined by seroma, surgical changes or clips, and consensus derived anatomic boundaries:

- cranial border: highly variable based on patient anatomy and position. The cranial border may not be a straight line and the lateral aspect may be more cranial than the medial aspect. RTOG defines this as "clinical reference + second rib insertion."

- caudal border: Clinical reference plus loss of CT apparent breast tissue (we use 2.5 mm cuts).

- Anterior border: Skin

- Posterior border: Excludes pectoralis muscles, chest wall muscles and ribs.

- Lateral border: Clinical reference and mid-axillary line which excludes the latisimus dorsi muscle

- Medial border: Sternal-rib junction depending on clinical anatomy. This border should not cross the midline.

- Breast PTV consists of the breast CTV + 7 mm expansion, edited to avoid the heart and to not cross the midline. A PTV_Eval is also created since the PTV will extend beyond the patient. The PTV_Eval is used to evalute the dose to the PTV and is defined as anterior to the anterior ribs and 5 mm deep to the skin.

- The lumpectomy bed is defined as that area apparent on CT and/or delineated by surgical clips. This is not a true "GTV," but is a CTV. The final CTV is created by expanding the lumpectomy bed by 1.0 cm to create the CTV. The lumpectomy CTV is constrained by anatomic limits which are pretty consistent with the breast volumes described above and does not cross the midline. In other words, the lumpectomy CTV is limited to the breast CTV definition, above.

- The lumpectomy PTV is created by a 7 mm expansion which is edited to exclude the heart. Further, the lumpectomy PTV may extend beyond the breast tissue. To evalute the PTV dose, a PTV_EVAL structure is created which confines the PTV to the breast which eliminates skin buildup region from the DVH and constrains the dose evaluation to the CPE region of the field.

- Note: the PTV_EVAL is a dosimetry evaluation parameter and is not to be used to determine beam port definitions. It is a dosimetric volume only.

Dose quality measures are the same for IMRT or 3D-CRT:

- PTV-EVAL 95% isodose is > 95% of the volume treated (PTVeval 95% > 95%)

- Dose homogeneity: V105 < 10% of the volume (V105 < 10%)

- The absolute hot spot < 110% IDV (V110 = 0%)

Nodal Volumes

Axillary nodes are divided into 3 levels, roughly correlated with the pectoralis minor muscle. The nodes lateral and inferior to the pectoralis minor muscle are level I axillary nodes, deep to the muscle are level II nodes and medial/superior to the muscle are level III nodes. The EBCTCG meta-analysis

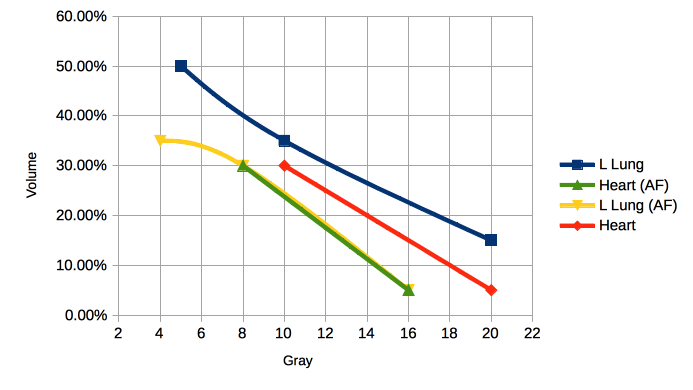

Organs At Risk — Standard Fractionation and Accelerated Whole Breast Irradiation Techniques

Breast organs at risk are the heart, ipsilateral lung, contralateral lung, contralateral breast, thyroid and spinal cord. Dose to these organs should be strictly limited.

| Organ | Standard Fractionation | AF-WBI |

|---|---|---|

| Contralateral Breast | Maximum Dose 3 Gy - < 5 Gy. | ≤ 2.4 Gy |

| Contralateral Lung | V5 ≤ 10% -15% | V4 ≤ 10% - 15% |

| Ipsilateral Lung | V20 ≤ 15% V10 ≤ 35% V5 ≤ 50% |

V16 ≤ 15% - 20%, V8 ≤ 35% - 40% V4 ≤ 50% - 55% |

The Cavity Boost

The need for a cavity boost is still debated. Recent retrospective data suggests that patients with demonstrated positive surgical margins have high local control rates without a boost. Fisher questions the need for a breast boost at all. Most authors report local recurrences within 2 cm of the original tumor site. These series report 60 - 80% recurrences after breast conservation → radiation are in and around the primary tumor site. Haffty et al suggests that these data are a strong reason to consider a tumor bed boost, and this is reflected in the ACR appropriateness criteria. Higher dose has been shown to be associated with greater tumor control at 10 years with a recurrence rate of 17% in unboosted patients compared with 11% with 5 - 15 Gy boost. In patients with unknown surgical margins, the boost cut the in breast failure rate in half from 9 - 20% to 6 - 11%. Others advocate for selective application of boost. In cases where there were clear margins with a re-excision, (pathologically demonstrated negative margins), the in breast failure rate was 7.6% (control rate of 92.4%).

The Lyon Breast Cancer Trial conducted a randomized study enrolling patients with Stage I/II breast cancer ≤ 3 cm treated with lumpectomy to clear margins, ALND and 50 Gy at 2 Gy/fraction, ± 10 Gy boost to the tumor bed. They found at 3.3 years, 5 years median follow up, the failure rates were 3.6% (3.3 years), 4.5% (5 years). More patients failed at 7 years.

Bartelink reported the EORTC trial randomizing Stage I/II patients to 50 Gy @ 2 Gy/fraction ± 16 Gy boost in 8 fractions. At 5 years the actuarial rates of local recurrence were 7.3% (no boost) and 4.3% (with boost), p < 0.001. Patients under 40 benefitted most, with a LRR5 of 19.5% without boost and 10.2% with boost. This study, updated at 10 years median follow up, a significant benefit was demonstated for all groups with a hazard ratio of 0.59 in favor of boost.

Electron beam direct fields are most commonly used today. Patient positioning may be modified to provide as flat a contour for an en face field as possible. The usual electron energies are between 8 and 16 MeV. Physical exam or imaging can be used to determine the correct depth for treatment. Treatment is usually given to the D90 isodose volume, but no deeper than the chest wall to decrease lung dose. The treatment field is the post-lumpectomy cavity plus 2-3 cm. In the pre-imaging days, the cavity scar was a surrogate for the lumpectomy cavity. A study demonstrated that scar guided hypothetical plans covering the scar plus a 3 cm margin failed to cover the entire excision cavity adquately in 62% to 53.8% fo the cases using pre- and post-treatment CT imaging.

Regional Lymphatic Irradiation Techniques

Matching the various beam divergences is technically challenging. There is controversy associated with the various methods of treating the regional breast lymphatics. Contemporary CT guided 3d imaging demonstrates a wide variety in anatomic distribution of the regional lymphatics. Frequently, the Level I nodes will overlap the humoral head, a structure spared in 2D block design. Repositioning the arm to angles less than 90 degrees would permit sparing the humoral head in the supraclavicular field.

Mean depths of axillary nodes:

- Level I: 4.6 cm (tangents cover)

- Level II: 5.1 cm (high tangents cover most)

- Level III: 3.6 cm (SCF)

Generally in the CT based 3dCRT era, the nodes should be contoured based on best available clinical imaging data and covered appropriately.

Supraclavicular field

The inferior border of the SCF must be matched to the tangent fields. The match line is usually just below the head of the clavicle. This anatomic landmark is palpated and a wire is place transversely across the chest to meet the mid-axillary wire. The gantry is angled to move the beam away from the cord about 10-15 degrees away from the field toward the contralateral side. A full SCF field is between 7 and 9 cm wide. If the entire axilla is to be treated, the field is extended laterally to the lateral aspect of the humoral head, or as identified on DRR contour projections. The humoral head is blocked. The inferior border is half beam blocked to prevent divergence inferior into the tangent fields.

The total dose of the SCF is 46 Gy to 50.4 Gy at 1.8 - 2.0 Gy/fraction to d=3.0 cm. Again, conformal 3dCRT should be used to delineate and cover the SCF nodes based on CT imaging anatomy for the patient.

Axillary lymph nodes

When the axilla is to be treated, the SCF is extended laterally to cover the tissue inferior to the outer 1/3 of the axilla. The dose to the axillary midplane is calculated at a dose point 2 cm inferior to the mid-clavicle. If the patient has unfavorable anatomy, a posterior axillary boost may be necessary, but generally it is not.

The PAB field is a small field and and there is significant controversy concerning the need for the PAB. Higher energy SCF beams may be able to provide coverage without a PAB when the patient's body habitus is significant. Alternatively, the axillary nodes can be contoured, a depth determined and a different depth dose prescription point can be chosen consistent with the patient's anatomy.

Internal Mammary Nodes

The IM nodes are difficult to treat due to their substernal location. In all cases the techniques used irradiate substantially more tissue. The nodes themselves are rarely the point of local-regional failure.

The most common field is a direct anterior field matched to modified tangents. This field originated with post-mastectomy radiation techniques. The rising contour of the medial aspect of the intact breast alters the dosimetry at depths of 4-5 cm. Including the IMN in the tangent fields using partial wide tangents substantially increases the volume of lung treated, as well as potentially increasing cardiac doses significantly in left sided tumors. The medial border is mid-sternum. The lateral border is 5-6 cm lateral to the midline.The superior border is matched to the SCF. The inferior border is the xyphoid or higher, generally the first three intracostal spaces are an approximate anatomical landmark (i.e. to the top of the 4th rib). If only the IMN is to be treated, the top border is the first intercostal space (superior border of the head of the clavicle). The field may be angled to match the incidence of the tangent fields. Electrons with careful planning can reduce the dose to underlying structures (lung and heart). Electrons in the range of 12-16 MeV are commonly used for at least a portion of the treatment.

If partial wide tangents are to be used the tangent crosses the mid-line 3 - 5 cm to cover the IMN in the first 3 intracostal spaces. to minimize cardiac and lung doses a block is used at the deep edge of the tangents blocking the inferior portion of the nodes. The most consistent doses to the IMN is with the use of partial wide tangent technique, and the most appropriate balance of tissue sparing and target coverage when irradiating the chest wall and IMN.

Severin at the Cross Cancer Institute (Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2003;55(3):633-644) compared various techniques for IMN coverage and normal tissue irradiation volumes. She reported on these techniques:

| Technique | Left Breast Dose | IMN Dose | Left Lung Dose | Heart Dose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard | 94.7% | 38.4% | 13.9% | 6.7% |

| Photon/Electron Match | 98.4% | 86% | 24.3% | 19% |

| Partial Wide Tangents | 96.5% | 99% | 22.8% | 10.3% |

CT based planning for treatment of the breast is particularly important. The internal mammary vessels are surrogates for the IMN chains and can be readily seen on CT images.

Field Matching

Due to the complexity of breast field arrangements, a number of field matching techniques have been developed and are in common use. The fields that need to be matched most commonly are the opposed tangent fields and the supraclavicular field. If an appositional electron field is used to treat internal mammry nodes, that too must be matched to both the tangents and the supraclavicular field. All of thes matches pose significant technical challenges with beam angles, divergences in two or more planes being taken into account.

Matching Tangents to Supraclavicular Field

In the past field match line fibrosis and rib fractures were much more common due to the technical limitations of 2D planning and accelerator limitations. With modern equipment, these problems are more easily overcome and the match line problem is now rare.

The pertinent beam geometries include the divergence of the supraclavicular field inferiorly into the tangent field. By placing an inferior half beam block at the central axis the lower border of the supraclavicular field becomes non-divergent. Now that the supraclavicular field border is known, the tangents must be adjusted to avoid superior divergence of the beam paths.

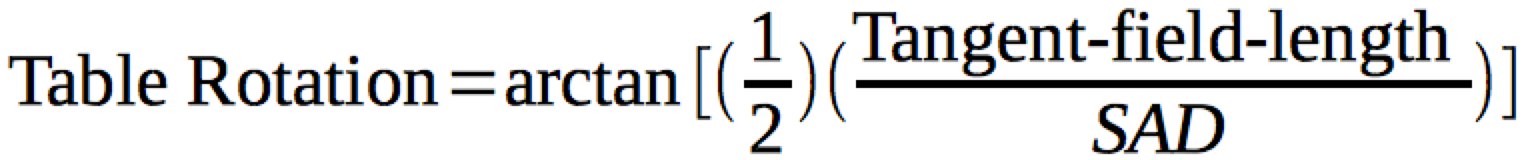

To correct for superior divergence of of the tangents into the supraclavicular field, the table is rotated to match the superior edge of the field with the inferior edge of the Anterior field. This will require a table rotation away from the gantry (patient's feet move opposite the gantry). Most modern treatment plans have built in calculations to determine the appropriate rotation for the match line, which is calculated from the trigonometric relationship:

For most patients the typical tangent field is about 20-25 cm, but is highly variable. This gives a table rotation (patient's feet away from the gantry) of about 7° .

A second technique for matching tangent to supraclavicular field is to set half beam block for the SCF as described above, and, using a single isocenter half beam block the superior half of the tangent field. This technique has the advantage in that it simplies treatment setup significantly, thus minimizing potential match line errors. It has a disadvantage that the inferior divergence doubles and may introduce extra dose to the superficial aspect of organs deep to the inferior edge of the beam. A second limitation is the maximum field size of the accerator is reduced in half, but this is not generally a problem in most breast setups. As most accelerators now have independent assymetric jaws, the deep edges can be matched using half beam blocking and setting the isocenter at the deepest most portion of the field (~ 2 cm central lung depth).

Matching Tangents to each other

Matching superior and inferior tangent borders is relatively straightforward, with a simple opposed field reasonably close at the isocenter, a deep aspect half beam block can be used to prevent divergence into the chest. If this setup is used the beam isocenters are directly opposed and blocks can be drawn easily. An alternative used at Michigan in days gone by used an "overrotated tangent" technique where the deep, diverging edges of the beam can be used. With this technique, the divergent edges of the beam are aligned with the lateral and midline wires on the CT images by deflecting the isocenter superiorly to give a non-diverget edge across the wires. The tangent isocenters are not directly opposed with this technique.

All breast setups should be inspected clinically before starting treatment to insure the treatment planner and systems have achieved matchlines and setup parameters correctly, and that field overlap/underlap has been corrected.

Tissue Compensation

Breast sites have considerable and highly variable surface inhomogeneity. In the past this has been corrected to provide a uniform tissue dose free of hot and cold areas by adding beam spoilers or wedges. These techniques carry disadvantages. Wedges harden the beam and increase the effective energy of the beam. Spoilers do not do as good a job compensation as more modern techniques. Before the advent of programmable multi-leaf collimation, tissue compensators were cut based on either surface imaging (Moire Camera) or CT based contour and electron density mapping. Then "step compensators" were cut mechanically and placed in the beam path. Modern accelerators are capable of programmed MLC adjustments in real time with selective beamlet attenuation during treatment. This allows a much more homogenous dose distribution by "shading the beam" a little bit in volumes of increased dose, and allowing more beam where the area is cold. This method is also called "forward planned IMRT." While the term forward planned IMRT is probably technically correct, the goal and I think a better term is compensation, as that is the goal: to compensate for tissue irregularities. Dosimetry using tissue inhomogeneity corrections is mandatory to use these techniques. The overall dose uniformity goal is to acheive a dose of between 93% and 105% in the treated volume.

Accelerated Partial Breast Irradiation

APBI in highly selected, very low risk patients may be reasonable. Omission of radiation therapy has been unequivocally demonstrated in numerous trials to compromise local control and to a lesser extent, breast cancer mortality. Prior to the publication of the START A/B and NCIC data, the NRG (NSABP and RTOG) B39/0413 studies were developed to examine the role of BID hypofractionated partial breast radiation. The study permitted both DCIS and invasive cancers. The techniques included accelerator based treatment or alternatively brachytherapy. Brachytherapy usually consisted of the Mammosite balloon or multiple needle implants. The early results for invasive cancer have demonstrated acceptable toxicity, to date. The ACR recommends in its appropriateness critera that APBI be restricted to older women with small, well differentiated tumors, ER positive for whom anti-estrogen therapy is planned. The dose for external beam APBI is 38.5 Gy in 10 BID fractions, for HDR, 3.4 Gy to 34 Gy in 10 BID fractions.

ASTRO has also created a consensus guideline dividing patients into 3 groups: Suitable, Cautionary and Unsuitable:

Suitable: Must meet all critera to be considered suitable

- Age ≥ 60

- BRCA 1/2 not present

- Stage T1

- Tumor size ≤ 2 cm

- Margins > 2 mm

- Any grade

- No LVSI

- ER positive

- Unicentric only

- Clinically unifocal with total size ≤ 2 cm

- Histology IDC or other favorable subtypes

- EIC or pure DCIS not allowed

- Associated LCIS ok

- pN0, SNB or ALND mandatory

- No neoadjuvant therapy permitted

Cautionary Group: Any of these critera should invoke caution and concern when considering APBI

- Age 50 - 59 years

- Tumor size 2.1 - 3.0 cm

- Stage T0 or T2

- Margins close (< 2 mm)

- LVSI limited or focal

- ER negative

- Multifocal: clinically unifocal with total size 2.1 - 3.0 cm

- Histology ILC

- Pure DCIS ≤ 3 cm

- EIC ≤ 3 cm

Unsuitable: These patients should only be offered APBI on an clinical trial if any of these factors are present

- Age < 50

- BRCA 1/2 present

- Tumor > 3 cm

- T-stage T3/T4

- Margins positive

- LVSI extensive

- Multicentric disease present

- Multifocal disease present with microscopic multifocality > 3 cm or clincially multifocal

- Pure DCIS > 3 cm

- EIC > 3 cm

- N positive disease

- Nodal surgical staging not performed

Organs at Risk — Dose and Volume Constraints (Emami, and RTOG 1005)

The original dose volume constraints were arrived by a survey by Emami on then current clinical practices. The development in the past three decades of highly conformal 3d treatment planing and sophisticated treatment planning techniques and analytics has led to the development of constraints on tissue that are volume and dose dependent.

Organs at risk in breast cancer treatment and their dose limitations for early breast cancer should meet the following critera. Note, that if more than tangents are required (ie nodal regions must be treated) then these parameters should be modified to meet the expanded field criteria.

| Organ | Dose-Volume Limit | Reasonable Variance |

|---|---|---|

| Ipsilateral Lung | No more than 15% exceeds 20 Gy | No more than 20% exceeds 20 Gy |

| Ipsilateral Lung | No more than 35% exceeds 10 Gy | No more than 40% exceeds 10 Gy |

| Ipsilateral Lung | No more than 50% exceeds 5 Gy | No more than 55% exceeds 5 Gy |

| Contralateral Breast | Maximum dose must not exceed 3.1 Gy No more than 5% exceeds 1.86 Gy |

Max dose < 4.1 Gy and no more than 5% exceeds 3.1 Gy |

| Contralateral Lung | No more than 10% exceeds 5 Gy | No more than 15% exceeds 5 Gy |

| Heart — Left breast | No more than 5% exceeds 20 Gy | No more than 5% exceeds 25 Gy |

| Heart — Left Breast | No more than 30% exceeds 10 Gy | No more than 35% exceeds 10 Gy |

| Heart — Right breast | No volume may get more than 20 Gy | No volume gets more than 25 Gy |

| Heart — Right breast | No more than 10% exceeds 10 Gy | No more than 15% exceeds 10 Gy |

| Heart | Mean heart dose must not exceed 4 Gy |