Prostate Cancer General Concepts

Cases

Prostate Anatomy

Prostate anatomy is based on zone. There are four zones, periphera, transition, central and anterior fibromuscular stroma. These zones are histologically distinct, with the anterior fibromuscular stroma zone being an anterior band of fibromuscular tissue contiguous with bladder muscle and the external urinary sphincter. The central zone surround the ejaculatory ducts. The peripheral zone is dominent in younger men while the transition zone is more prominent in older men. Enzymes including PSA and acid phosphatase are secreted into the seminal flid. PSA is produced by benign and malignant prostate cells. PSA production is influenced by the presence of testosterone. PSA measurement is influenced by a number of factors including prostatitis, digital rectal exam or endorectal ultrasound transducer insertion or MRI coil placement. PSA should be measured before these procedures to insure accurate PSA readings.

The surgical anatomy of the prostate is interesting in that the neurovascular bundles run superio-laterally and inferior-superiorly. They come close at the prostatic apex. Nerve sparing surgery becomes difficult in this region while attempting to achieve wide margins, increasing the risk of positiv apical margins. Efforts to increase the margin in this area can also result in a forshortened external sphincter increasing the risk of incontinence. Extracapsular extension is the cause of most non-apex positive margins. Johns Hopkins aregues that focal penetration of the capsule in the setting of low grade disease is not clinically significant, but penetration into the surrounding fat of 1 cm is a major unfavorable prognostic indicator. Conversely, the Mayo Clinic data suggests taht patients with GS ≥ 7 experience an increased risk of recurrence regardless of margin status.

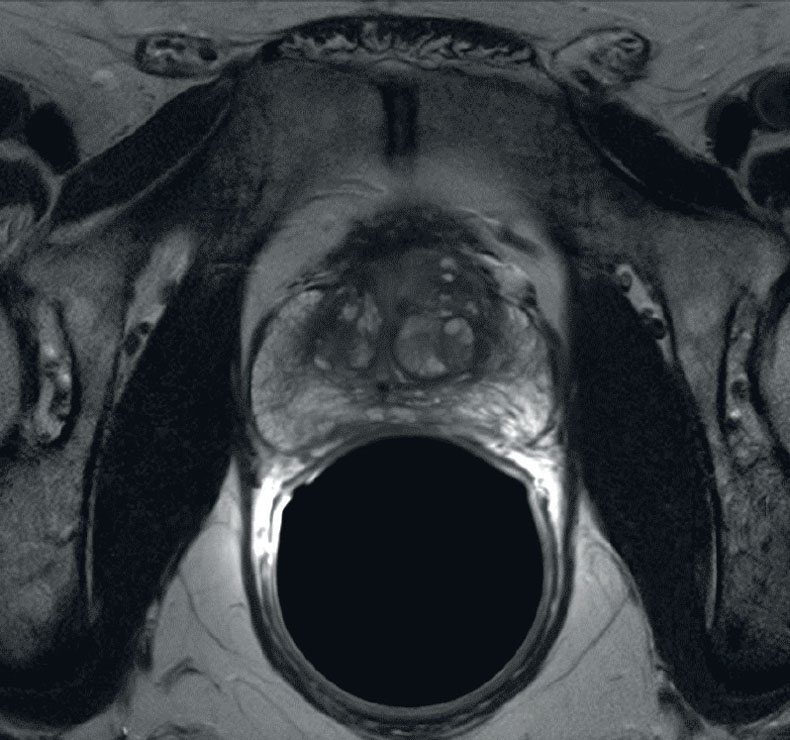

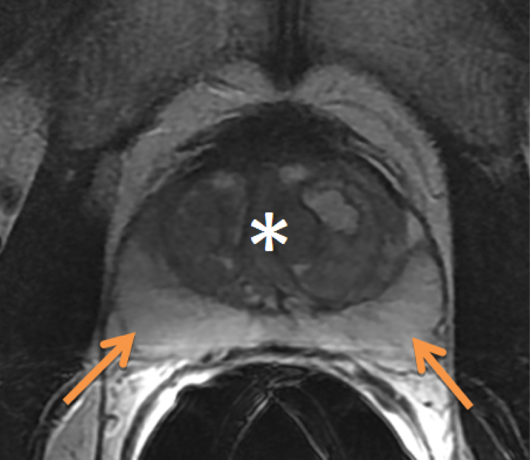

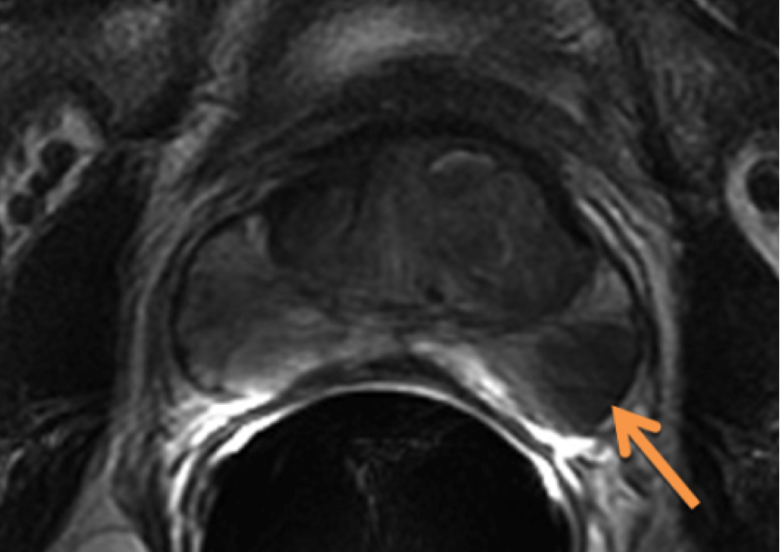

MRI Anatomy of the Prostate

|  | |

|

|

|

Epidemiology

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer in men. The frequency is higher in men of African-American men but rantes aorund 20% lifetime risk. The cancer specific mortality is 5%. A large spike in prostate cancer was seen in the early 1990s, then leveled off. Age adjusted mortality was highest in that same time frame and has been slowly declining since then. Prostate cancer mortality was 30,200 in 2002 with 189,000 new cases. In 2008, 241,740 cases were diagnosed, but the death rate declined to 28,170.

In recent months, the role of PSA screening has been called into question, along with a recommendation that PSA screening be sharply limited in the US by the USPSTF. There are two studies which conflict. The American study randomized 77,000 men prospectively into screened and unscreened groups and showed no difference on relatively short followup. Of note, the non-screened population were treated for prostate cancer nearly at the same rate as those nost screened, confounding the study's results. A European study of 182,000 men had a 70% higher rate of treatment in the screened group. This study concluded there was a 20% reduction in death in patients screened and treated for prostate cancer.

Risk Factors

Age is the most important risk factor. Prostate cancer incidence increases with increasing age. Incidence in men 40 - 49 years is 1:38; for men 60 - 69 years 1:15 and for men over 70 1:8. Autopsy data from Detroit demonstrated 70% of men > 80 and 40% of men > 50 years had pathologic evidence of prostate cancer. The median age at diagnosis is 68 with incidence increasing sharply with increasing age.

Prostate cancer is low in Asian men, highest in Scandinavia. In the US, African-Americans have higher incidence and mortality.

Androgen exposure over time maythe risk of prostate cancer progression and development, but this is not certain. Men deficient in 5α-reductase are rarely affected by prostate cancer or BPH. Evidence supporting hormonal influence includes two large randomized trials involving the use of 5α -reductase inhibitors. The Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial was a large scale population based trial using finasteride (Proscar) which lowers DHT. This study demonstrated a reduction in prostate cancers in a trial of 18882 men ≥ 55 with normal DREs and PSA ≤ 3.0 ng/ml. The prevalence of prostate cancer was reduced by 25% in the finasteride arm of over the placebo arm. The study also showed that the prevalence of intermediate and high risk (GS 7-10) was higher in the finasteride arm. A second similar study used dutasteride (Avodart) and enrolled based on age and PSA 2.5 - 10.0 ng/ml, with a negative biopsy. This study showed similar results: the risk reduction in prostate cancer was 22.8% but the cancers that were diagnosed showed a clear trend toward higher GS (8 -10). Roach cautions that a myriad of factors associated with increase risk, including vitamins, alcohol consumption, dietary fats have simply not been demonstrated to impact the development of prostate cancer or its natural course.

The risk of death from early prostate cancer is about 10% at 10 years from diagnosis for early stage, low risk, low volume disease. In late 2013 and early 2014, there has been increasing advocacy for active surveillance. However, the general progression of early local prostate cancer to bulky disease approaches 50% at 10 years and the risk of death increases substantially. Androgen deprivation therapy alone is not a curative therapy although it may slow the progression of disease.

Natural History

Prostate cancers are predominantly found in the peripheral zone. BPH generally develops in the transitional zone. Tumors are also found in the fibromuscular stroma. Larger tumors are seen posteriorly near the capsule. Multifocal disease is seen in 77% of prostate specimens, Secondary cancers are mostly small. An increasing frequency of chromosomal abnormalities correlated with PIN and progression from PIN to adenocarcinoma. When lymph nodes were involved, there was usually evidence of one or more foci of the primary having similar chromosomal abnormalities. Prostate cancers are both multicentric and heterogeneous. It is possible that a single focus of prostate cancer may determine its overall behavior, which may be missed by straight reliance on the biopsy histology. This also raises the question of significance of a tertiary Gleason pattern in predicting prostate cancer.

Transitional zone tumors tend to have a lower frequency of extracapsular extension with high volumes of disease and higher PSA levels but remain confined to the prostate. These tumors may have a favorable prognosis despite PSA values ≥ 10 ng/ml. Studies have shown that these TZ cancers can be large, are sometimes not found on biopsy (only 63% were initially biopsy confirmed positives) and 80% had organ confined disease. More than 1/3 had volumes > 6 cc. Compared with peripheral zone tumors, in a case match by volume, there were no differences in Gleason grade 4/5, serum PSA or prostate volume, but differences in stage and organ confined disease were significant. Peripheral zone cancers had an actuarial 5 year biochemical freedom from failure rate of 49.2% while TZ cancers the rate was 71.5%.

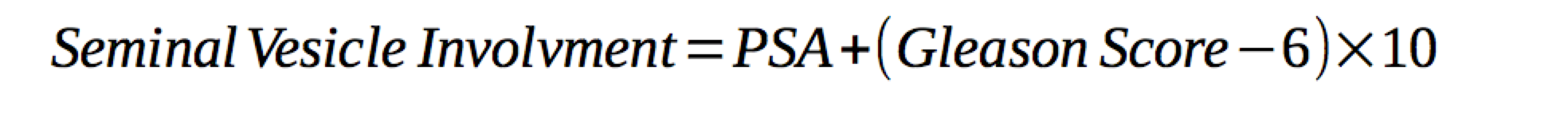

Pre-treatment PSA is predictive of extra-prostatic extension and seminal vesicle invasion. The rate of organ confined prostate cancer ranges from 53% to 67% with PSA < 10 ng/ml. Organ confined disease rates with PSA 10-20 ng/ml drops to 31-56%. PSA < 4 ng/ml have low involvement of the seminal vesicles.

| PSA | Organ Confined | SV Involvement | Pos. Surgical Margins (RP) |

|---|---|---|---|

| < 4 | 53 - 67% | None | 11% |

| 4 - 10 | 53 - 67% | 6% | 20% |

| 10 - 20 | 31 - 56% | 11% | 33% |

| 20 - 40 | — | 36% | 56% |

| > 40 | — | 42% | 63% |

|

|

|

Lymphatic Involvement

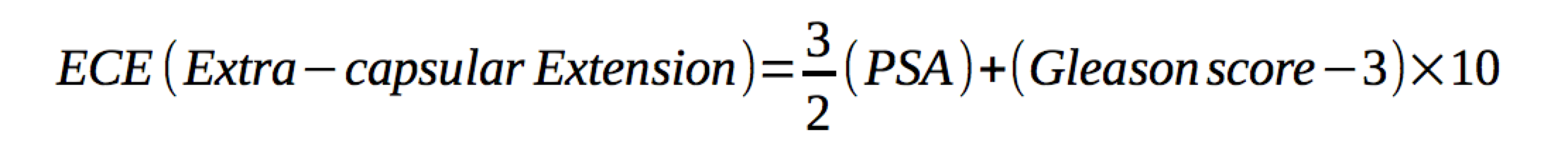

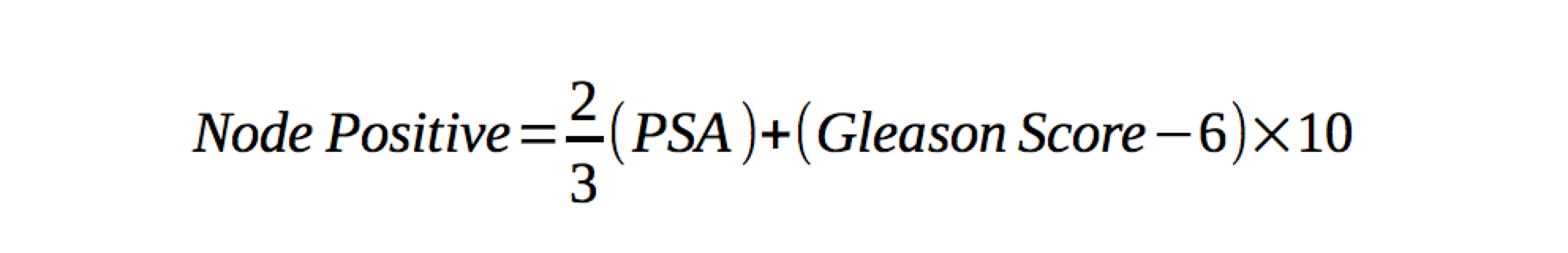

Tumor size and grade predict lymphatic involvement. Early stage (T1 and T1) cancers have led to a decreased incidence of lymphatic involvment at diagnosis. In low risk cancer, the risk of LN disease is thought to be < 10%. Partin developed tables and a nomogram for predicting nodal involvement risk. His nomogram includes clinical staging, pre-treatment PSA and grade. Prognosis is closely related to degree of lymphatic involvement. Patients with multiple lymph node involvement had increased risk of death as contrasted to those with no or a single node positive. The risk of nodal involvement can be predicted by the Roach equation 2/3PSA+10(GS-6).

Prostate cancer is generally multifocal with frequent perineural invasion. The first path of spread is into the seminal vesicles. It then extends through the capsule into the periprostatic fat. From there it travels to the pelvic lymphatics. The areas at risk include the obturators, external iliac, presacral and

Although treatment of lymphatics is controversial, there are studies that have demonstrated an advantage to treating the pelvic lymphatics. These include the University of Michigan, Yale, and Milan. Although these are retrospective studies. UCSF concluded that patients with lymph node involvement risk of > 15% based on the Roach equation benefited from pelvic nodal irradiation. An older RTOG study was re-analyzed and demonstrated similar results. According to Roach, the group with the greatest benefit was in the intermediate nodal risk group (5%-15%).

Contrasting this, a Fox Chase center failed to show an advantage with Whole pelvis radiation therapy. Leibel's text speculates that this failure to show an advantage may be due to the fact that they only included higher risk patients. Leibel supports this by citing RTOG 9413 nodal treatment criterial which none of the Fox Chase patients would have met. The RTOG 9413 data showed that there was a dependence on field size. A subset analysis of 9413 showed there was a clear relationship between field size and the benefits of whole pelvic radiation over prostate only radiation. The RTOG covered the nodes up to the top of the true pelvis including the common iliacs, while Fox Chase covered only the lower pelvic lymphatics. A French Study (GETUG) similarly did not show an advantage to treating pelvic lymph nodes and has been criticized for the same reasons that the Fox Chase study has been criticized: superior border at S1/S2, lower median PSA (12 v. 22 ng/ml) and about half of the patients had a "Roach" computed lymph node risk of < 15%. In addition, radiation doses where changed during the study from 66 Gy to 70 Gy, further confounding results.

Patients with node positive disease were found to have a > 85% risk of distant metastases at 10 years compared with < 20% at 10 years with 0 or 1 node.

RTOG 9413 accrued patients with:

- localized prostate adenocarcinoma

- PSA ≤ 100 ng/ml

- Stratification by T-stage, PSA and Gleason Score

- Estimated lymph node risk > 15%

RTOG 9413 randomized patients to:

| Arm 1 | NAH + Prostate Only radiation |

| Arm 2 | NAH + Prostate Radiation + Pelvic Radiation |

| Arm 3 | Adjuvant Hormone Therapy (after RT) + Prostate Radiation |

| Arm 4 | Adjuvant Hormone Therapy (after RT) + Prostate Radiation + Plevic Radiation |

The median PSA was 22.6 nl/ml, 67% had T2c - T4 disease and 72% had GS 7 - 10. PFS failure was defined as first occurence of local progression, regional nodal failure, distant metastases, biochemical failure or death from any cause.

At 5 years median followup, the pelvic radiation arm was better at 54% v. 47% in the prostate only arm. Likewise, neoadjuvant hormones plus pelvic radiation achieved 60% progression free survival. Overall survival has not yet been reported due to the long followup interval. The greatest benefit suggested was to patients with intermediate and high risk disease. (i.e. GS7, PSA < 20 ng/ml or GS6 & PSA> 30)

UCSF recommends whole pelvic radiation only for patients felt to be at significant risk:

- histologic confirmation of node positivity

- documented seminal vesicle involvement

- risk of lymphatic involvement > 15%

- GS ≥ 7 and > 50% of biopsy positive or predominantly GG 4 (4+3) disease, or e.) GS 6 and clinical T3.

Clinical Workup

Traditionally (pre-PSA) the DRE was used in screening. It is not particularly sensitive nor specific. Only 25 - 50% with an abnormal DRE have cancer. Prostate cancer can be asymptomatic until attaining a significant size and patients with palpable tumors are more likely to have advanced disease than those who do not. DRE screening is 70% sensitive and 50% specific when used alone. When combined with PSA 40% are not palpable and 70% are confined to the prostate. More recently controversy over the use of PSA screening from the EORTC ERSPC study of men aged 50 - 74 years randomized to no PSA screening or screening once in 4 years with annual DRE in both arms. At 9 years, the PSA screening showed a modest redution in death requiring 1410 men screened with treatment of 48 men to produce this reduction. The reduction in death rate was only apparent in men 55 - 69 years. A US study looked at annual screening for 6 years with DRE compared with no screening. At a median follow up of 7 years no difference in mortality was noted. The USPSTF recommends no screening in men ≥ 75 years and questions the value in younger men. The AUA continues to recommend annual screening in all who have a life expectancy > 10 years and age > 40.

The PSA half life is 2.2 days, and manipulation of the prostate by DRE or other means can transiently elevate the PSA. For this reason, PSA screening should be performed prior to a DRE. Further, benign conditions can also cause elevated PSA.

There is a volume effect on PSA with increased PSA seen in larger prostates. Acute or chronic inflammation can also elevate the PSA. The positive predictive value for PSA ≥ 4.0 ng/ml is between 31 - 54%. There is much debate on the clinical significance of small tumors detected with PSA screening. One author suggests that clinically insignificant prostate cancer is a cancer that gives rise to no more than 20 cm3 by the time of expected death, which when combined with Gleason score based on age. A review of pathology revealed that most men undergoing treatment for prostate cancer were appropriate, having clinically significant prostate cancer. In Seattle, an estimate of 15% white and 37% blacks were overdiagnosed based on a SEER review, while conversely in Göteberg, Sweden, a PSA random study did not result in overdiagnosis of clinically insignificant prostate cancers: most cancers would develop into clinically significant or lethal prostate cancers.

PSA detected cancers may be smaller, but in the Netherlands, 60% of screening detected cancers contained areas of higher grade disease (Gleason grade 4 or 5) and 50% had a Gleason Score of 7. The study suggests that most of these are clinically important. Prognosis based on natural history and treatment course in non-palpable prostate cancers:

- Untreated non-palpable disease: 6.5 years median survival free of intervention

- 33% rate of intervention at a median of 2.7 years

- Increased PSA density and decreased percentage of free PSA correlated with progression of disease.

PSA velocity has been correlated with higher frequency of aggressive cancers. A rate of rise > 0.75 ng/ml-year has been associated with a higher frequency of cancer. A rate of rise > 2.0 ng/ml-year prior to diagnosis is correlated with greater prostate specific mortality following radiotherapy or radical prostatectomy for localized disease.

Staging Workup

The NCCN has specific staging work up recommendations based on pre-treatment PSA, Gleason Score, DRE findings. Patients with localized prostate cancer are often asymptomatic. Prior to PSA detection, prostate cancer was found with a nodule on DRE, urinary signs (obstructive uropathy) Obstructive uropathy is manifest by hesitancy, decreased stream, post-void dribbling due to prostate cancer impinging on the membranous urethra. Chronic obstruction and bladder distention can lead to decreased detrusor muscle compliance leading to urinary frequency, urgency and nocturia. Occasionally prostate cancer is diagnosed with TURP for urinary signs (T1a - ≤ 5% or T1b - > 5% of tissue resected )

A complete clinical history including IPSS scoring. The IPSS quantifies urinary signs and symptoms associated with prostate disease. A examination including a digital rectal exam are mandatory. Note the size of the gland, consistency and nodularity. About half of the palpable nodules are found to be cancer on biopsy. Abnormal DRE or consistently elevated PSA are indications for TRUS. 12 cores are presently taken most frequently. If there is obtructive uropathy, then a transitional zone biopsy may be indicated.

Once biopsy confirmed, additional workup may be indicated. Baseline laboratory data includes the PSA value, testosterone level to establish a reference, and chemistries (in anticipation of androgen deprivation therapy where indicated).

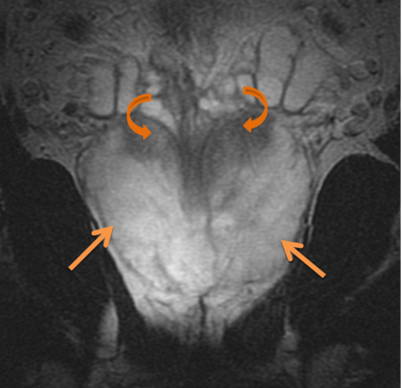

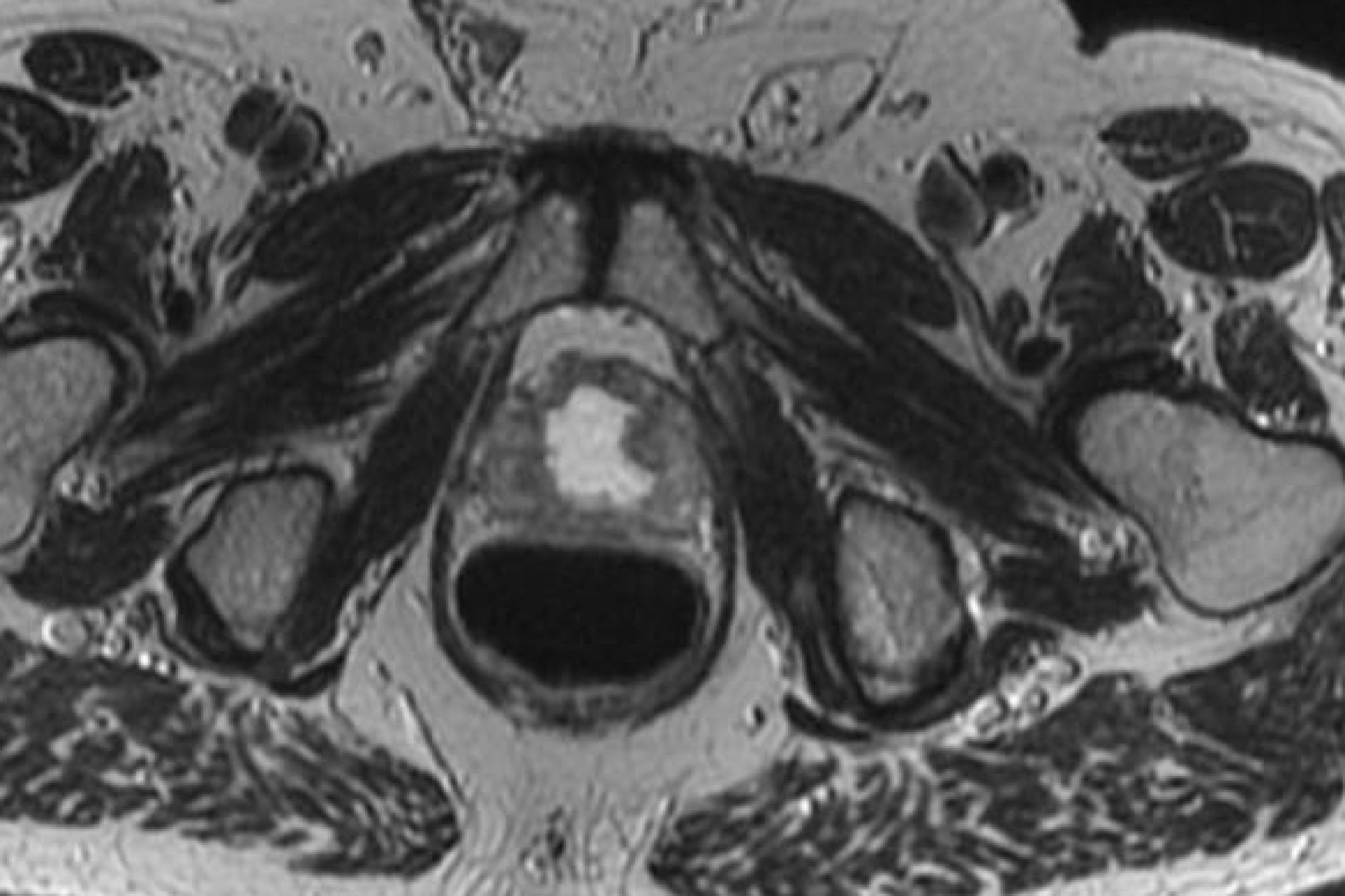

Imaging

Additional imaging studies include an MRI of the prostate, generally with endorectal coil. If the PSA is > 20 then a bone scan is reasonable. A transrectal ultrasound is an intrinsic part of the biopsy in recent years. Peripheral zone cancers can be seen on the ulltrasound with hyper-echoic lesions in 69% of the cases. CT of the pelvis and prostate are used in radiotherapy treatment planning. Discrepancies between CT and MRI on fused images may exist (Roach):

- Non-contrast CT defined volumes are 32% larger than MRI defined volumes

- Roach identified four areas:

- posterior aspect

- posterior-inferior aspect

- prostate apex

- neurovascular bundles

- MRI was superior to CT in identifying the apex, neurovascular bundles and anterior rectal wall

Bone scans are not generally required in asymptomatic early stage, low PSA patients. The yield is low unless PSA > 20 ng/ml or there are complaints of bone pain. A pre-treatment bone scan may be useful in patients to establish a baseline to discriminate arthritic changes from later development of boney metastases.

Risk Stratification

There are two risk stratification schemes. Both have similarities, in that they are divided into low, intermediate and high risk groups, based on Gleason Score, pre-treatment PSA, and extra-prostatic disease. The NCCN scheme (D'Amico) is most commonly used:

| Risk | PSA | Pathology | Stage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Risk | ≤ 10 ng/ml | GS ≤ 6 | T1c-T2 |

| Intermdiate Risk | 10-20 ng/ml | GS 7 | |

| High Risk | > 20 ng/ml | GS ≥ 8 | T3 |

D'Amico studied pre-treatment prostate cancer clinical and pathologic predictors of time to post-operative biochemical failure for Stage T1c/T2a and pre-treatment PSA < 10 ng/ml. The 5 year failure free survival were not statistically different for GS 2-6 v. 7 (3+4) but were statistically different for GS 7(4+3) and GS 8-10. Biochemical control at 5 years was 79% (GS 2-6), 81% (GS 7=3+4), 62% (GS 7=4+3) 18% (GS 8-10). A JHU study examined GS 7 (3+4) v. (4+3) and found that predominant Gleason grade 4 number of positive cores, age and stage corresponded pre-operative PSA and biopsy Gleason Scores.

The location and volume of prostate cancer were also prognostic. Transition Zone cancers were physically isolated from the neurovascular bundle and ejaculatory ducts and thus had better prognosis than peripheral zone tumors. Stanford identified volume of Gleason Grade 4/5 cancer and peripheral zone location as significant predictors (cancer volume ≥ 6 cm3).

General Management and Treatment

The natural history of prostate cancer is variable, even when accounting for known prognositc indicators: PSA, Gleason Score, age, Gleason Grade patterns and volume of cancer present. Even when these groups are analyzed by low, intermediate and high risk, there is variabiliy within the groups. The treatments are not without sequalae. In the United States and elsewhere there is ongoing debate concerning the role of PSA testing, whether prostate cancer should be treated and if so, which subset. Life expectancy and quality of life should be discussed frankly with the patient and his family, along with all prognostic information so that the patient may arrive at an informed decision on what course to pursue.

Based on current studies and available data, there are no significant differences in the biochemical and disease free survival for early stage disease treated with radical prostatectomy, external beam radiation therapy or interstitial brachytherapy. There are wide geographic variations in patterns of care in the United States for early prostate cancer. More recently the NCCN consensus guidelines flow sheets (Rev. 1.2014) for low risk (GS ≤ 6, PSA < 10, Stage T1-T2a) and intermediate risk (GS 7; PSA 10-20 ng/ml, Stage T1-T2a) suggest the equivalence of active surveillance, EBRT, Brachytherapy and Radical Prostatectomy. For high risk (GS ≥ 8, PSA > 20 ng/ml), very high risk disease, the NCCN states there is Category I (high level evidence): supporting Radiation therapy and long term androgen deprivation therapy.

Based on the newly published Swedish prostate cancer study of watchful waiting v. treatment, it seems increasingly clear that there is beneift for treatment of prostate cancer in terms of delayed morbidity and survival, with the number needed to treat to achieve benefit continuing to drop over time from 24 to 8. (See Active Surveillance Section)

Radical Prostatectomy

Surgical removal of the prostate using either open retropubic, perineal or robotic assisted surgery. The most common procedures are retropubic or robotic prostatectomies which include the ability to access and sample pelvic lymph nodes. The procedure consists of complete excision of the prostate, the surrounding capsule and the seminal vesicles, ampulla and vas deferens. The urethra is excised at the protato-membranous junction leaving no prostate tissue at the apex. The surgical robotic assisted prostatectomy is a laparoscopic procedure. The complication rates and biochemical control rates at 5 years are similar with freedom from biochemical failure at 5 years 88%. The incidence of positive margins were similar with each approach. 7 year biochemical disease free survival rates were 85% (T2/T3a) and 43% (T3b — seminal vesicle invasion) disease.

Sequalae and Complications of Treatment

Active Surveillance

There are some who are candidates for active surveillance. Men who have limited life expectancy (≤ 10 years), low volume disease (< 5%) low Gleason Scores (GS &e; 6) and low PSA (< 10 ng/ml). A recent update of the Swedish Mens Prostate Cancer study (NEJM SPG-4) concluded that compared with watchful waiting, radical prostatectomy in the pre-PSA era (1989-1999) reduced all cause mortality, prostate cancer specific mortality, distant metastases and the need for androgen deprivation therapy. The authors note that despite this, a large percentage of the watchful waiting group have not required any palliative treatments. They note that the number needed to treat to prevent one death has continued to decrease from 20 in the initial study to 8 in the present update now at 23+ years of follow up. The relative risk of death in the surgically treated group was 0.53 compared with the watchful waiting group. The absolute difference was 11% in favor of treatment, which in this study was exclusively surgical.

Radiation Therapy

Radiation Therapy has been very successfully used in the treatment of both localized and metastatic prostate cancers. In localized disease, the treatment is usually of curative intent. Forman, Olson and others have used external beam radiation therapy with curative intent with some success (anecdotal reports) even in cases where there are oligometastases, although the failure rates are high. Further Olson, Kwan and others have advocated for definitive treatment of Stage IV prostate cancer with radiation to the prostate where IPSS scores are elevated based on the knowledge that prostate cancer can cause obstructive uropathy including blockage of the membranous urethra.

3D conformal and IMRT to the prostate are now standard and offer significant advantages over prior treatment techniques (4 field). These include the ability to safely escalate the dose by limiting dose to organs at risk, thus minimizing sequalae of radiation. Prostate brachytherapy using permanent implant 125I and 103Pd has demonstrated excellent local control either alone or when combined with external beam radiaiton therapy.

External Beam Radiation Therapy

3d-Conformal and IMRT radiation therapy are presently the mainstays of prostate radiation therapy. By carefully controlling organ at risk doses (OAR) morbidity of treatment is substantially improved over prior 4 field techniques. Advanced imaging techniques including MRI-CT fusion allow better defintion of target volumes, when combined with good immobilization and real-time visualization techniques to account for bladder/rectal filling. By precisely visualizing the prostate in the treatment planning phase and its location and deformation in the treatment delivery phase, safe dose escalation can take place. (Some would argue that dose escalation is a compensation mechanism for geo-spatial misses due to previously undetected prostate motion.)

Intensity modulated radiation using computer controlled multi-leaf collimation has become well developed and is commonly used to provide tight dose-volume delivery and concave isodose volumes needed to fully cover the prostate while avoiding excess dose to rectum, bladder and bowel.

Initial Setup and Simulation

The prostate position and sometimes shape are variable, depending on rectal filling and bladder filling. It is imperative in the high dose treatment era that the prostate be well localized to avoid underdosing the margins of the prostate and overdosing the immediately adjacent tissue. This means control of the prostate position by controlling the bladder filling and rectal emptying.

There are several schools of thought on the best pre-simulation preparation. One school is to have the patient do a bowel prep the evening before simulation which will empty the rectum. The simulation is then performed using bowel contrast agents with the rectal lumen visualized by intra-rectal contrast. The patient is treated in the supine position with alpha-cradle/vac-loc immobilization devices. Some centers use intraprostatic fiducial markers (primarily in the US, less often in Canada). Other centers believe that CT imaging is generally adequate with IV contrast for visualization of the prostate when combined with real-time image guidance (IGRT) without the need for fiducials. There are various fiducials in use, most commonly gold seeds or helicoil types. The helicoil types are thought to be less prone to migration during treatment. CT imaging is obtained through the region of the prostate with adequate extension to allow radiation therapy beam coverage using IMRT beam placement or 3D-conformal techniques, generally 6-field or 7 field.

Other centers do not use special bowel preparation other than to ask that the patient empty his rectum and fill his bladder prior to simulation. This is felt to be more reproducible on a day to day basis since the patients will not comply with daily bowel preps during the course of treatment. Further, these centers generally use real time imaging (tomotherapy or cone beam ct or older techniques such as BAT ultrasound or fiducial marker placement) and image guided radiotherapy immediately prior to radiation delivery with real-time adjustments to correct for intra-fraction prostate postion changes. Using these techniques, prostate position, rectum emptying and bladder filling can be seen prior to treatment delivery and if necessary, the treatment can be delayed to allow the patient to empty his rectum and fill his bladder to more closely approximate the simulation study and insure the radiation field covers the desired target volumes and avoids the desired avoidance volumes. With modern high speed, high resolution CT scanners, the use of intra-rectal contrast may not be needed, and unless contrast agents, if used, are sufficiently dilute, may interfere with inhomogeneity corrections used in beam dosimetry calculations. The RTOG recommends simulation with bladder full, supine, with images ≤ 3 mm cuts, and recommend, but do not require urethral contrast. CT slices should be taken from the top of the iliac crest to the perineum.

Once the patient setup and imaging are complete, an isocenter can be chosen and marks can be placed on the patient's skin and treatment planning can commence.

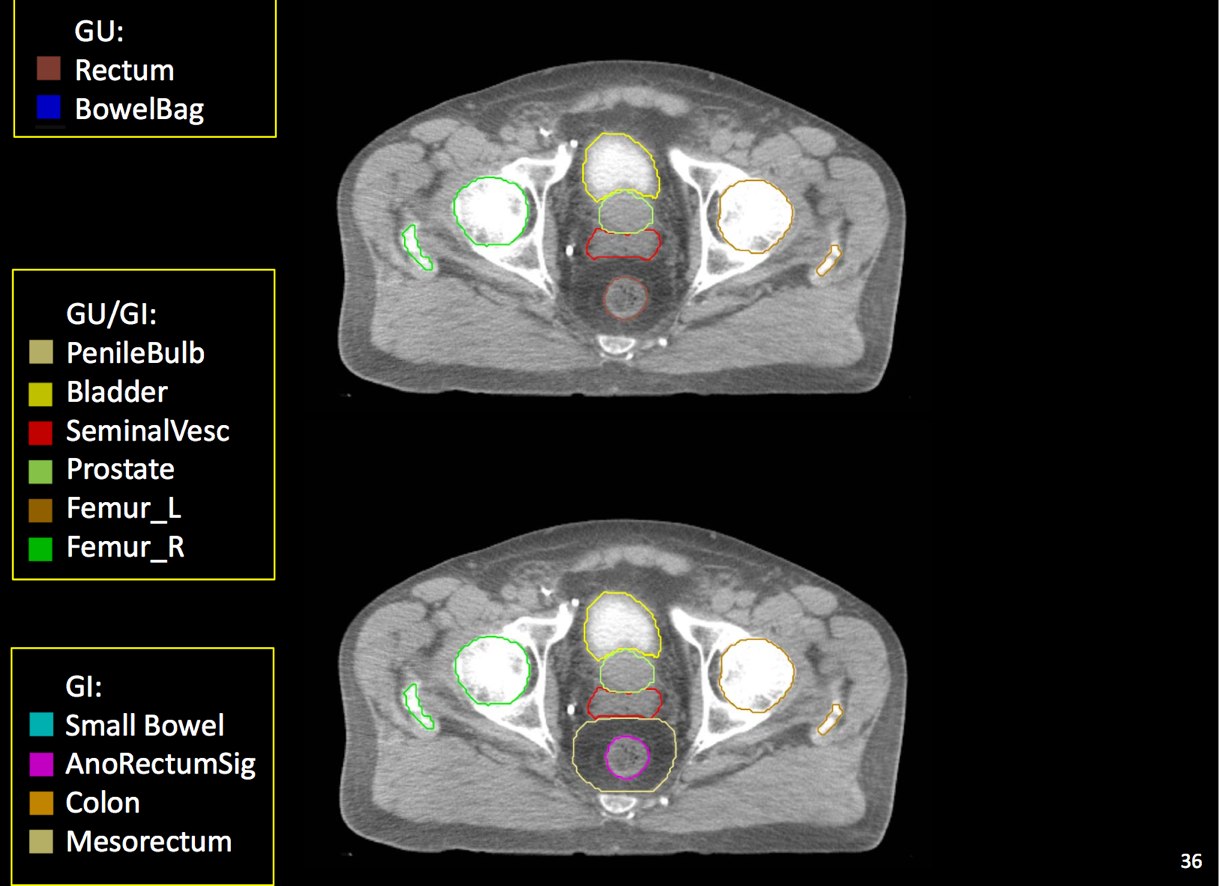

Target Volume and Organ at Risk Volume Contouring

At a minimum, the following contours should be available to the planners:

- prostate

- seminal vesicles (treat at least proximal if risk calculated > 15% --ucsf)

- pelvic lymphatics (if treatment indicated -- risk > 15% -- ucsf)

- femoral heads

- rectum

- bladder

- bowel (where necessary due to bowel prolapsing below the bladder)

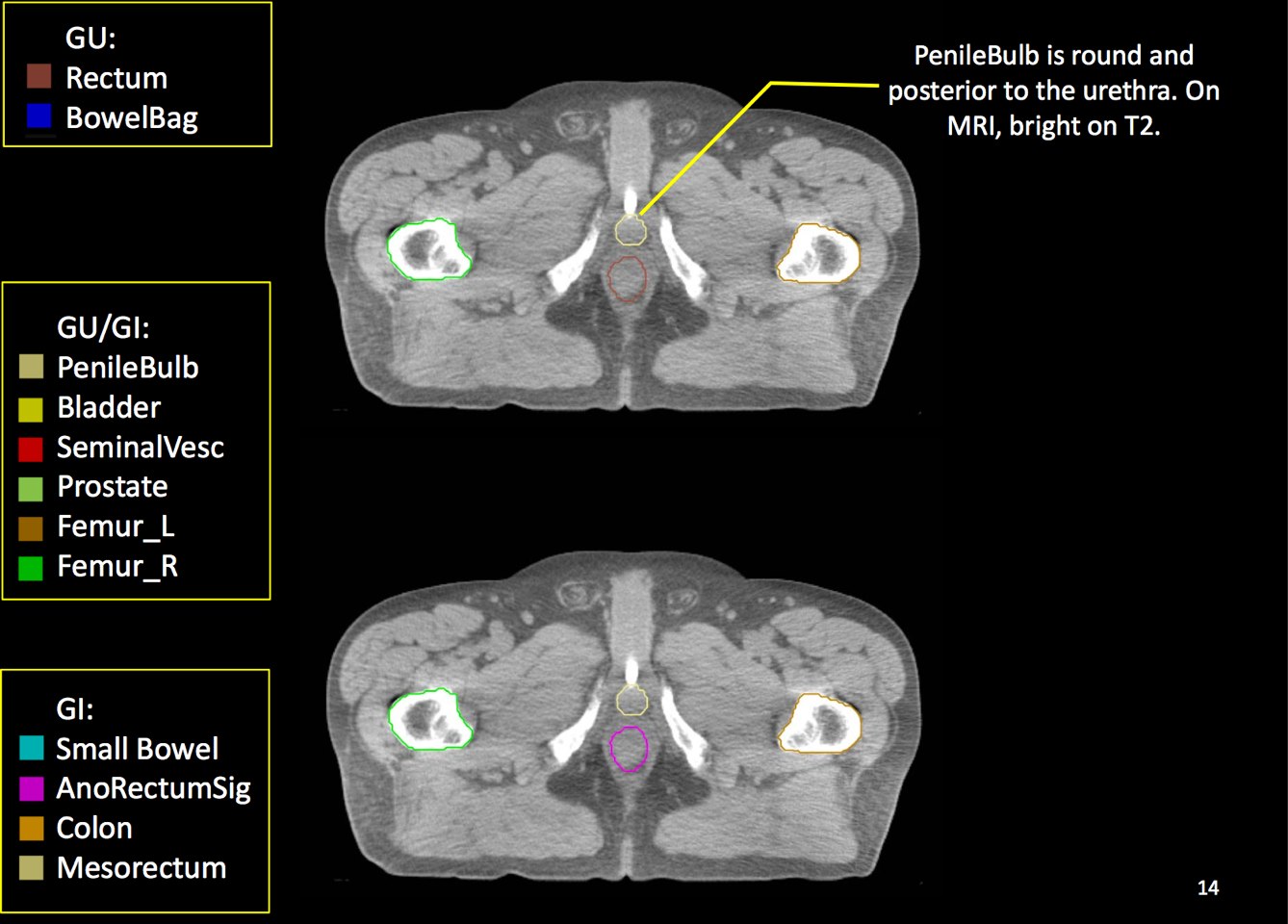

- penile bulb

The target volume (CTV) is defined as the prostate and seminal vesicles. The planning target volume expands the CTV to take into account setup uncertainties, both systematic and physiologic. By using daily image guidance, where available, physiologic parameters are more controlled and allow the reduction of CTV expansion required to fully cover the prostate and adjacent tissue at risk.

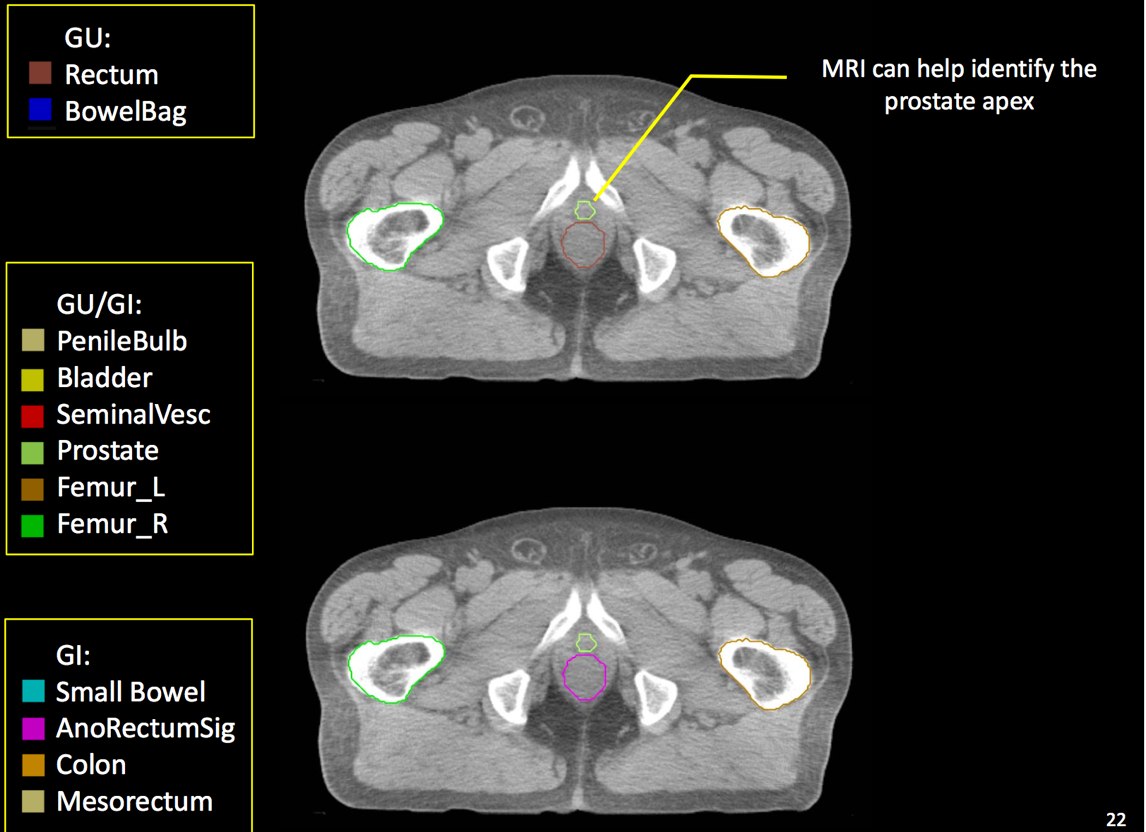

Anatomic delineation of the prostate and the apex using CT has not been without controversy. To attempt to resolve this several methods of identifying the apex were used:

- retrograde urethrogram

- CT (treatment planning)

- MRI prostate

Poor correlation of the prostate apex was found between these modalities. The retrograde urethrogram was tested to insure that the urethrogram itself did not displace the prostate by pre- and post-urethrogram MRI studies which demonstrated no artifactual displacement as a result of the urethrogram. Roach examined 10 patients and noted that the prostate volume was 32% larger on non-contrast CT than when determined by MRI. The regions of most non-agreement were posterior-inferior (neurvascular bundles) and posterior extent of the gland. The CT volume for prostate and seminal vesicles was 40% larger on the average than the MR with the CT variant 8 mm larger at the base of the SV and 6 mm larger at the apex. This was corrected for and persistent with interobserver variation.

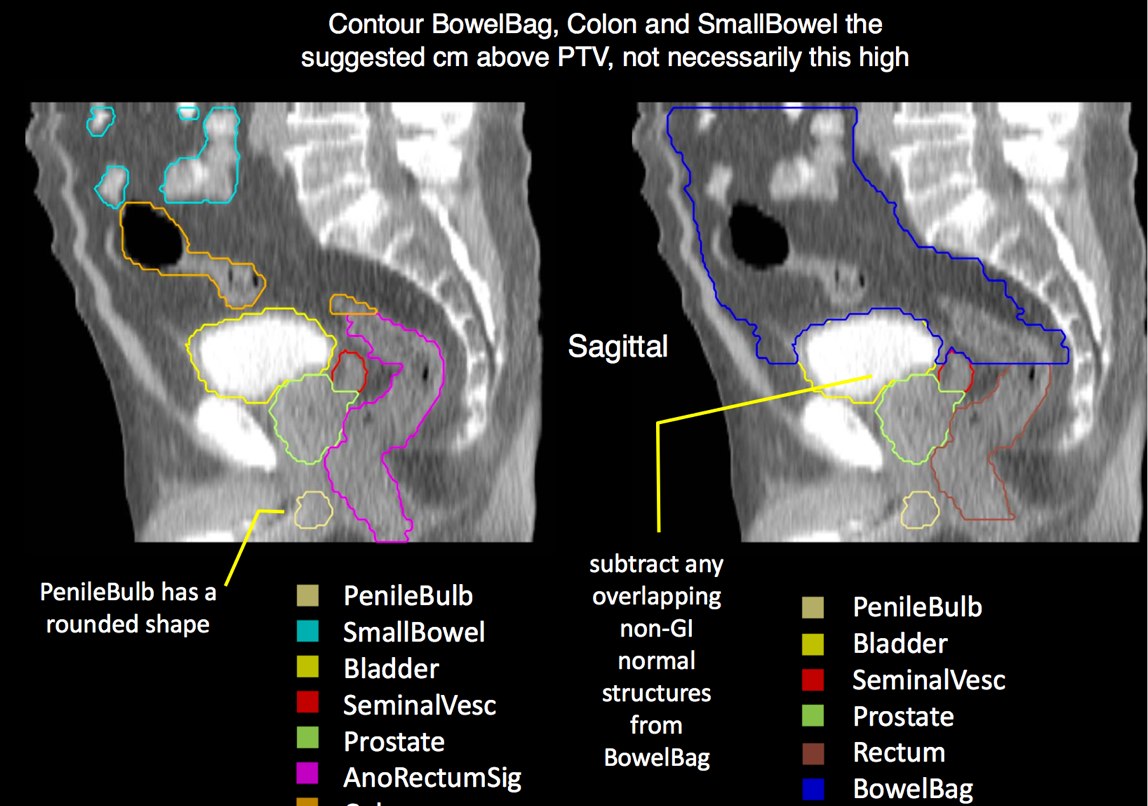

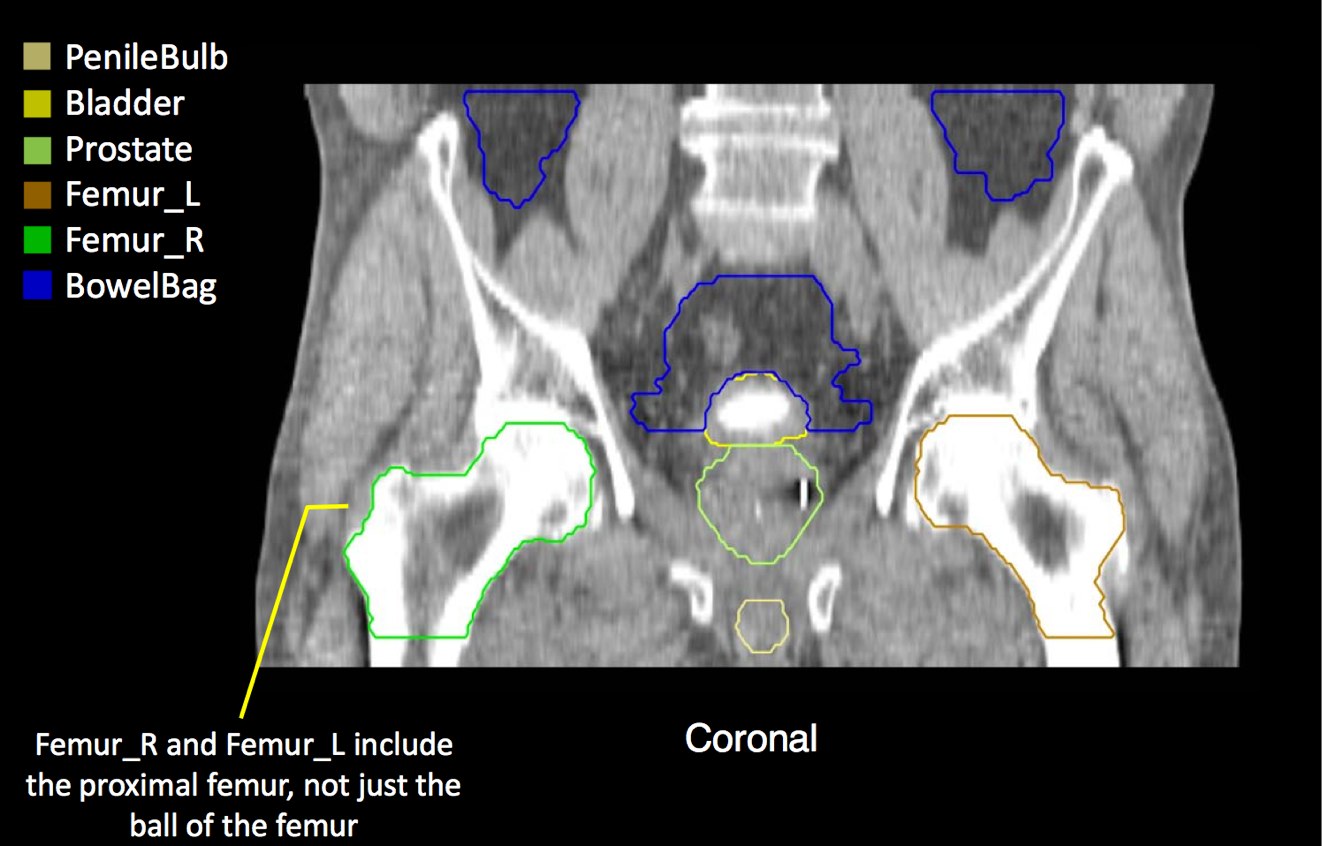

There is significant variation of contours and techniques. The apex and base are regions most susceptable to variation. 3D perspectives help signficantly reduce this variation using transverse, sagital and coronal projections to determine the true extent of the prostate. More recently contouring atlases have been developed by the RTOG with grant assistance from the NCI and are available here. The following images are obtained from the RTOG contour atlases as an excerpt demonstrating areas of potential uncertainty.

A standard template 6 field pelvis plan has been used at University of Michigan and Wayne State University with highly conformal beams using a 7 mm margin. Most plans today are IMRT plans with image guidance. The 6 field pelvis consists of opposed lateral fields, and anterior and posterior oblique beams.

IMRT planning uses inverse planning to deliver conformal dose to target while avoiding organs at risk. Careful delineation of OARs is important. Recently, advanced use of knowledge of radiobiologic dose-volume toxicity data (pre-Quantec and Quantec) has become more important in limiting toxicity while insuring adequate dose to the target volume. These data are used to identify treatment volume constraints. The constraints vary by organ and volume of tissue treated. (See Quantec Pelvis discussion)

Target Volume Doses

MSKCC uses 81 Gy at 1.8 Gy/day for a target dose to the prostate. NCCN recommendations include 75.6 Gy to 79.2 Gy for low risk cancers with higher doses (to 81 Gy) for high risk disease. Moderately hypofractionated doses are also considered reasonable at 2.4 to 4 Gy/day as a alternate to conventionally fractionated radiation. Patients with high risk disease are also considered candidates for pelvic node irradiation, along with neoadjuvant, concombinant and adjuvant androgen deprivation.

RTOG protcols currently use 79.2 Gy in high risk disease at 1.8 Gy/fraction. Dose volume constraints to the PTV are 95% minimum dose, to 107% maximum dose (volume at least 0.03 cm3 to avoid a single voxel point dose artifact). Beam energies should be ≥ 6 MV

UCSF recommends a minimum dose of 78 Gy to the prostate unless there are significant medical contraindications, at 2 Gy/fraction. The seminal vesicles are treated to 54 Gy at 1.8 Gy/fraction. When treated, the pelvic lymphatics are treated to 45-46 Gy at 1.8 - 2 Gy /fraction.

More recent RTOG studies (0815,1115) use dose escalation. For high risk cancers where lymph nodes are at risk, using either 3D-CRT or IMRT the pelvic lymph nodes are treated to 45 Gy at 1.8 Gy/fraction, including the prostate and seminal vesicles. Dose homogeneity should be 95% - 110% with an absolute dose variation limit of 44-46 Gy at 98% coverage. A boost to the prostate and proximal seminal vesicles to an additional dose of 34.2 at 1.8 Gy/fraction is used for a total dose to the prostate of 79.2 Gy. Boost field homogeneity is 10%

GTV is the entire prostate. If a urethrogram is used, the apex is designated at the visualized prostate or 5 mm superior to the tip of the urethrogram dye. The initial field encompasses the pelvic lymphatics from L4/L5, pre-sacral nodes from L5-S1 and inferiorly below the prostate by 5 mm. The internal and external iliac nodes should be covered below the SI joints. Lateral fields should include the posterior extension of the seminal vesicles. The usual posterior border is S2/S3, but this may vary based on CT imaging and imaging should take precedence. The inferior extent of the internal iliacs are the tops of the femoral heads, the inferior extent of the obturator nodes is the top of the pubic symphysis.

CTV construction is a selective expansion on the prostate GTV. For the lymphatic portion of treatment, the CTV should be a 7 mm expansion around the contoured vessels, corrected for anatomical barriers. The nodal CTV expansion should not extend outside of the true pelvis, into muscle, bone or organs such as bladder, rectum and bowel. Treatment will be to the PTV planning target volume which will consist of a minimum of 0.5 cm expansion on the CTV and a maximum expansion of 1.5 cm in all dimensions.

The final boost PTV is an expansion from the prostate and seminal vesicles CTV/GTV: The CTV is the prostate and areas at risk for harboring disease, and the proximal 1 cm of seminal vesicles, unless the SV have biopsy confirmed disease, in which case the entire SV may be treated, with adjustments as necessary to maintain dose limits to OAR. The PTV expansion is selective. Superior and inferior margins should be 5-10 mm, based on CT imaging thickness and inter-slice distance, as well as the confidence in the setup reproducibility, and the availability of image guidance. Radial expansion is between 5 - 10 mm with some centers using 7 mm for rectal (posterior) aspect, and 10 mm elsewhere. It may be necessary to replan the patient if daily CBCT imaging or other high quality image guidance demonstrates a significant variance with the imaging used for planning.

Organs at Risk DVH Constraints

Retrospective analysis have demonstrated rectal toxicity (bleeding) had significantly higher rectal wall dose-volume histograms than those who did not. Rectal and bladder doses are a function of dose and volume carried to that dose:

| Organ Limit | 15% volume or less receives more than | 25% or less receives more than | 35% or less receives more than | 50% or less receives more than |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bladder | 80 Gy | 75 Gy | 70 Gy | 65 Gy |

| Rectum | 75 Gy | 70 Gy | 65 Gy | 60 Gy |

| Penile Bulb | Mean dose ≤ 52.5 Gy | |||

There are recent efforts to standardize segmentation names for radiotherapy treatment planning. This is encouraged to allow for inter-institution comparisons, particularly on protocol patients, but it may also assist institutions in comparing dosimetry should additional radiotherapy or other dose questions arise. The normal clinical structures to be identified are:

- Bladder

- Rectum (rectosigmoid flexure/bottom of SI joints to inferior extent of the ischial tuberosities)

- Bilateral femora (including the proximal femurs to the inferior extent of the ischial tuberosities)

- Penile bulb

- Bowel as a bag (rather than individual loops if nodes are to be treated and bowel is within the primary field portals)

Brachytherapy

Brachytherapy may be used alone in favorable risk patients or combined with external beam radiation treatment. Pre-planned template loaded implants under ultrasound guidance are the rule, while in the past, intraoperative loading using ultrasound guidance has been used. Pre-planned implants give better quality dosimetry and loading patterns, and seed implant locations. The full process is:

- Determination of suitability

- TRUS determination of prostate volumes and shapes

- Generation of a computerized treatment plan with needle placement and source loadings

- Sources are ordered and received and the implant goes forward.

- The prostate is examined under anesthesia in the OR to verify consistency with the treatment plan

- Stabilization needles are placed in unloaded positions in the template to reduce prostate motion

- Needle loadings are modified if necessary due to prostate shape or volume changes to insure good coverage

- The needles are placed transperineally under TRUS guidance to deliver the prescription dose to the prostate

- The base and apex of the prostate should be re-examined during the course of the implant to insure prostate stability, position and distortion

- Post implant imaging is obtained to determine implant quality at a later date

Patient Selection Criteria

Brachytherapy patient selection is based on morbidity and risk. Contraindications to brachytherapy include metastatic disease (including nodal involvement), gross SV involvement, or T3 disease that cannot be adequately implanted due to geometry. Brachytherapy is not generally capable of treating seminal vesicles beyond 1 cm proximal to the prostate. Poor prostate geometry or high IPSS scores are relative contraindications. Generally, prostate volumes < 60 cc, IPSS scores < 12 are considered good candidates.If the prostate size is marginal, a trial of androgen deprivation may shrink the prostate enough to permit an adequate implant. It is important to assess pubic arch interference as a potential complicating factor in permanent implant cases. Pubic arch interference is the limiting factor in determining the ability to obtain a high quality implant, rather than the ability to obtain coverage in the prostate absent arch interference.

Prior TURP may also be a contraindication as this may allow seeds to overdose the urethra, which could lead to stricture or post-implant incontinence. With modern peripheral loading techniques, this may be less a contraindication than previously thought as complications have decreased. Linked seeds may be advantageous in this setting. Before any brachytherapy in a patient with a history of TURP can be considered, detailed imaging of the extent of TURP should be obtained and considered mandatory. T2 MRI and T1 post gadolinium will be helpful.

Dose and Isotope Characteristics

For brachytherapy alone, 125I or 103Pd are most often used. The prescribed doses are different to account for the differing isotope biologic characteristics.

- For 125I

- 144 Gy (brachytherapy alone) is prescribed to to the isodose volume that encompasses the prostate completely

- 110 Gy (EBRT boost combined modality) to the same volume as brachytherapy alone

- Source strength range is 0.277 to 0.650 U/source for 100 Gy doses

- For 103Pd

- 125 Gy (brachytherapy alone) to the isodose volume that encompasses the prostate completely

- 100 Gy (EBRT combined modality) to the same volume as brachytherapy alone

- Source strength range is 1.29 U to 2.69 U/source

No discussion about brachytherapy would be complete without discussing the physical characteristics of the radiation sources.

| 125I has a half life of 60 days and a mean photon energy of 27 keV and an initial dose rate of 7 cGy/hour. |

| 103Id has a half life of 17 days and a mean photon energy of 21 keV and an initial dose rate of 19 cGy/hour. |

No differences in tumor control has been identified, dosimetry has been found to be similar, and most studies have not seen a difference in toxicities. Patients in a randomized study (Pd v. I) noted increased radiation proctitis in the first month, but recovered sooner consistent with Pd's higher dose rate delivery and shorter half life. Source strength has not been shown to be a factor in outcomes and a wide variety of source strengths have been used. Most common for 103Pd 1.1 - 3.5 U have been used. The RTOG suggests source strengths be restricted to 1.29 U - 2.69 U. Dose is controled by increasing or decreasing the number of sources as necessary to achieve the treatment goal. Similarly for 125I, source strength recommendations are 0.29 U to 0.65 U/source.

Dosimetric goals should be confirmed by post-implant dosimetric evaluation. The goals of treatment planning and delivery adequacy of target coverage to V100 (volume of prostate treated to 100% of the prescribed dose), or D90 (dose delivered to 90% of the prostate). Dose to the urethra, rectum and bladder should also be examined.

Outcomes and Results

Surgery and Salvage Radiation

Due to referral patterns, the treatment of prostate cancer is somewhat disparate. While there has been an evolution in the selection of treatment, many are given surgery as a first option only. Recent revisions of the NCCN Guidelines (1.2014) for high risk prostate cancer have moved radiation therapy + androgen deprivation to Category 1 treament recommendations: Objective evidence of superior outcomes, and have lowered radical prostatectomy recommendations to those select few patients with extremely favorable characteristics, and even then most will require adjuvant radiation therapy.

A 1994 review of major surgical case series identified failure rates of 60% for T1-T2 disease undergoing prostatectomy based on biochemical failure at 10 years. The clinical failure rate was 25%. Shorter series show significantly high failure rates at 2-4 years post prostatectomy.

For stage T1-T2 disease 75% were free from failure at 5 years and 50% were free from failure at 10 years for prostatectomy alone patients. With higher Gleason scores, matters were significantly worse. For GS 8-10 had a failure rate exceeding 50% at 5 years. For GS 7 the surgical failure rate was 40%, with disease confined to the prostate. All others were worse. More recent reported improvements are due primarily to patient selection and adjuvant radiation therapy.

Patients with extracapsular extension which is about half of all surgical patients, have local failure rates of 25% - 68%. External beam radiation reduces the risk of recurrence after radical prostatectomy although there is no proven survival benefit. Factors in assessing the risk include the pre-treatment PSA, the pre-radiation PSA, and the post-surgical PSA doubling time. Post recurrence PSA > 1 ng/ml should be considered for neoadjuvant total androgen blockade prior to radiation therapy, due to a more unfavorable outcome.

EBRT: Biochemical Failure and survival

In pre-1994 series, the outcomes for radiation and surgery based on selective retrospective analysis appear to be similar at 10-15 years. Patients in the surgical series tended to have lower PSA, were younger and healthier than those in radiation series. A large percentage in the surgical cohorts had earlier stage (T1-T2) disease and many surgical series excluded node positive disease, as opposed to radiotherapy series which do not.

The Shipley Study

This was a large multi-insitutional study with a minimum 2 year follow up treated between 1988 and 1995 at 6 centers in the US. At the outset, 24% had PSA ≥ 20 ng/ml. At 5 years, the following results were seen:

| OS5 | 85% |

| Disease Specific Survival | 95% |

| Freedom from Biochemical Failure | 65.8% |

For patients with PSA < 10 ng/ml :

| Freedom from Biochemical Failure at 5 years | 78% |

| Freedom from Biochemical Failure at 7 years | 73% |

Of the patients who were free from biochemical failure at 5 years, 5% relapsed in years 5 - 8, indicating a very durable response to radiation.

3D-CRT and IMRT EBRT

Evidence for improved outcomes with IMRT and 3D-CRT is both prospective (RTOG) and retrospective. Dose escalation was associated with decreased risk of recurrence for doses in excess of 70 - 72 Gy (Pollack). Doses have been now set in the range of 78-81 Gy with improved PSA control for paients iwth PSA > 10 ng/ml. The freedom from failure curves comparing 70 v. 78 Gy appear to start to diverge at about 2 years with significant divergence by about year 7. At 10 years, the freedom from failure for 78 Gy was 70% v. about 50% for 70 Gy.

MSKCC divided prostate cancers into low, intermediate and high risk groups, with doses of 81 Gy. Actuarial 3 year PSA relapse free survival was:

| low risk | 92% |

| intermediate risk | 86% |

| high risk | 81% |

Note that this table is for 3 year control, while prostate cancer generally runs a much longer course.

EBRT ± ADT

D'Amico noted patients treated with neoadjuvant/comcomitant and adjuvant hormonal therapy had a significantly better outcome in GS 7 and above. There was also an improvement in cause specific survival for intermediate risk disease. Androgen deprivation alone had a signficantly worse overall survival than radiation + ADT.

Results of Standard Treatment

Radical Prostatectomy

Bianco reported long term outcomes of 1963 patients treated by one surgeon undergoing radical prostatectomy. Positive margin rate was 12%, 5 year biochemical control was 82% and 10 year biochemical control was 77%. Risk stratified outcomes were

| PSA Risk | Biochemical Freedom from Failure | Cause Specific Survival |

|---|---|---|

| PSA 4 - 10 ng/ml | 83% | 99% |

| PSA 10 - 20 ng/ml | 64% | 95% |

| PSA > 20 ng/ml | 47% | 95% |

Conventional EBRT for low risk disease

Kuban reported a large multi-institutional analysis of T1/T2 treated between 1985 and 1995. At a median follow up of 6.3 years, using conventional 2D treatment planning in the majority. 30% were treated with 3d-conformal radiation techniques. Radiation doses ranged from 60 - 78 Gy. Meedian doses for those treated with < 70 Gy was 67 Gy and for those > 70 Gy was 72 Gy. The control rates were:

| PSA Risk | Biochemical Freedom from Failure |

|---|---|

| PSA 0 - 4 ng/ml | 80% |

| PSA 4 - <10 ng/ml | 60% |

| PSA 10 - 20 ng/ml | 46% |

| PSA 20 - 30 | 34% |

Dose Escalated EBRT

Zeitman reported a trial of 70 Gy v. 79.2 Gy for stage T1/T2 pre-treatment PSA < 15 ng/ml, followed for a median of 5.5 years. He reports a PSA relapse free survival at 5 years of 61% in the low dose arm, 80% in the high dose arm. MSKCC reports (Zelefsky) on 2,551 patients which showed a 49% reduction in risk of biochemical failure for low risk patients.

| Risk | PFS (Biochemical, 10 y) | Distant Metastases at 10 years | Cancer Related Death |

|---|---|---|---|

| low | 81% | 0% | 0% |

| intermediate | 78% | 6% | 3% |

| high | 62% | 10% | 14% |